By: Ron Sims, Special Collections Librarian

Planning for the New Campus

Northwestern University's professional schools—Medical, Law, Commerce, Dental, and Pharmacy—were originally founded as separate schools and scattered in various locations throughout the city of Chicago. In 1902, with the exception of the Medical School, the schools were consolidated in a single Loop location in the Northwestern University Building (formerly the Tremont House) at Dearborn and Lake Streets. In 1915, the University began a search for a new campus that could accommodate all the schools in their own specialized buildings in one central location.

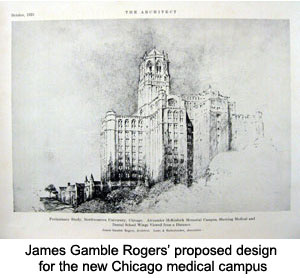

Through the efforts of University President, Walter Dill Scott and the “Campaign for a Greater Northwestern” in 1919, the University purchased nine acres of land along Lake Michigan in the near north side Streeterville neighborhood. University architect, James Gamble Rogers created a master plan for the major buildings to be erected there.

Through the efforts of University President, Walter Dill Scott and the “Campaign for a Greater Northwestern” in 1919, the University purchased nine acres of land along Lake Michigan in the near north side Streeterville neighborhood. University architect, James Gamble Rogers created a master plan for the major buildings to be erected there.

Rogers’ style is known as “Collegiate Gothic.” The vision was to have low buildings rising from Lake Shore Drive, with the pinnacle as the Medical Center building and Superior St. as a dead end at Fairbanks Ct., giving two full blocks to the new structures. As Daniel Burnham reminds us: Make no small plans!

The complex was the first “skyscraper” medical center in the world, housing the Dental and Medical schools, clinics and laboratories.

Mrs. Elizabeth J. Ward’s Gifts to Northwestern University

Mr. A. Montgomery Ward, one of Chicago’s mercantile giants, died December 7, 1913, leaving the bulk of his estate to his wife, Elizabeth J. Ward and his daughter, Marjorie Montgomery Ward.

Ten years later, in a letter dated December 13, 1923, Mrs. Ward conveyed her wishes to the University Trustees of her “desire to create a worthy and appropriate memorial” to her late husband.

She continued: “His life was largely devoted to devising and developing a new type of business and one which added a significant part in making Chicago a center of influence in the business world. His most conspicuous public service was in his long continued efforts to conserve the Lake Front for the use of the people.”

She further stated that the memorial should contain the following elements:

“It must be a visible thing which adds something to the values of the City.

It must be enduring.

It must be useful to the community.”

She noted that Northwestern was the first university founded within the City and was aware of the plans for construction of a new urban campus. In recognition of this, she offered a gift of $3,000,000 for the erection and endowment of a Medical Center, as a memorial to Montgomery Ward.

She noted that Northwestern was the first university founded within the City and was aware of the plans for construction of a new urban campus. In recognition of this, she offered a gift of $3,000,000 for the erection and endowment of a Medical Center, as a memorial to Montgomery Ward.

On the same day, another letter stated her “Deed of Gift” for $1,000,000 as an Endowment for the Medical Center. Great indeed as this gift was, and wide sweeping as it was in philanthropic circles, it was not the last. In March, 1926, another $4,000,000 was given to the University “for the improvement of the teaching of Medicine and Dentistry in the Medical and Dental Schools.”

Tragically, Mrs. Ward died on July 26, 1926 before the completion of the Memorial which she had only seen from the outside. At her private funeral, Walter Dill Scott, President of the University, described her as a “genuine … human, imbued with the highest ideals of service to humanity.”

In a public statement, Dr. Scott stated: “All who had had the privilege of knowing her had come to love her, and hoped that she would have many years to enjoy the fruition of the projects which were so dear to her … Mrs. Montgomery Ward has been the greatest of all our friends. This estimate on our part is not based on the fact that she made Northwestern University the agency through which she has invested in public welfare, but it is based on the spirit in which she made her investment and the purpose she sought to attain thereby.”

New Outpatient Clinics

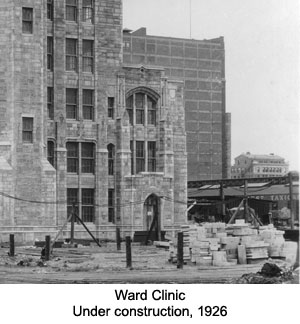

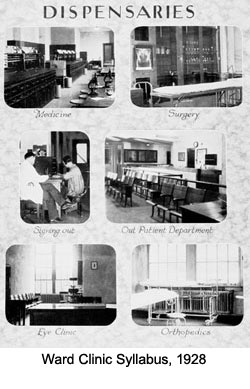

Specified in Mrs. Ward’s gift was a directive regarding civic duty, specifically “to render community health service." In response, an outpatient clinic department was constructed in the new building. The facility was named the Montgomery Ward Medical Clinic and comprised a three story “addition” on the west end of the Ward Memorial, with an entrance at 747 N. Fairbanks Court. (See the embedded video at the end of this article for a brief glimpse of the workings of the Medical Clinic.)

The October 24, 1927 medical school announcement noted the “[a]dequate accommodations … [providing] care of somewhat excess of 300 patients per day. The out-patient departments furnish clinical teaching material of the utmost value. Adequate equipment has been provided in all departments including X-ray, electro-cardiograph, metabolism and physiotherapy. More than 80,000 patients were cared for during the year 1926-27."

By 1934, there was an excess of 500 patients per day, with an annual total of over 157,000 patients per year.

The 1941 annual announcement noted “every effort is made to individualize the work of the student and to supply means of determining an accurate diagnosis … The assignment of a student [in] each [department] is of substantial duration to give the student a substantial knowledge of the disease entities encountered.” A wholly redesigned and equipped X-ray department was given through the generosity of Colonel Robert R. McCormick as a memorial to his late wife, Amy Irwin McCormick (1880-1939) in 1940.

In 1943, the Louis E. Schmidt Clinic for treatment of venereal disease was added, and the clinics were renamed the Northwestern University Medical Clinics.

By 1950, the X-ray clinic had been enlarged with additional equipment “to provide diagnostic and therapy facilities for the Clinics, Student Health and Research. Photo Roentgen equipment is available for chest survey of all new admissions to the Clinic and the students of the various Chicago Campus schools,” as noted in the 1951 annual announcement.

With the addition of the Morton Building in 1955, more space was added to the Clinic. Outpatient teaching was conducted in the clinics of Children’s Memorial Hospital, Evanston Hospital, Rehabilitation Institute and in several community-sponsored clinics.

The annual announcements in the 1960s noted the Social Services Department with responsibilities for teaching the influence of family relationships, cultural, and socio-economic factors upon the patient’s illness and recovery. Through seminars and individual case conferences, medical students were taught how to use casework services and community resources in meeting the environmental and family problems of the patient. Each senior student spent one full quarter in the outpatient clinics conducting his or her own office practice under the supervision of instructors. Comprehensive medical care was stressed.

By 1975, the long history of a dispensary service came to an end, as other units of the Medical Center provided aid on a private patient basis. Through the supervision of the Department of Community Health and Preventive Medicine, alternative clinics were made available to students on a volunteer basis, such as the Erie Clinic. Emphasis was placed on the importance of long-term ambulatory patient care, with students assigned for a longer term on an individual basis, conducting management as would a personal physician. Outpatient service was also made as an elective for senior students.

While another chapter in the history of the University came to an end, the next chapter began as students furthered their education through community-based healthcare facilities in cooperation with the members of the McGaw Medical Center.

Archival Footage of Northwestern University Medical School Clinic from Northwestern News on Vimeo.

Linked with the kind permission of Matt Paolelli.

This article is part of the current exhibit, Photographing Pediatrics, now on display in Dollie's Corner on Level 2 of the Galter Health Sciences Library. The exhibit includes a pictorial history of the dispensaries and clinics at Northwestern.

Updated: September 18, 2023