Austin Maurice Curtis, MD, 1868-1939

By: Katie Lattal, Special Collections Librarian

Austin Maurice Curtis was born in 1868 in Raleigh, NC, to Eleanora and Alexander Curtis. He attended college at Lincoln University, where he met his wife, Namahyoke “Namah” Sockum. They eloped in 1888, the year Curtis earned his BA. Curtis moved to Chicago to attend Northwestern University Medical School, and Namah joined him after her family found out she had married.

In 1891 Curtis earned his MD from Northwestern and became the first intern to serve at the newly opened Provident Hospital. He became the first Black physician to receive a staff appointment at a de facto white hospital when he was brought on as an attending surgeon at Cook County Hospital in 1896. While on staff at Provident and Cook County, Curtis maintained a private surgical practice. He became a highly respected surgeon due to the abundant and varied training he received while working at the hospitals and his mentorship under Daniel Hale Williams, an accomplished and renowned Chicago surgeon. Curtis followed in Williams’ footsteps when he succeeded Williams in the position of Surgeon-in-Chief at Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington, DC. Image at left: Curtis' medical school Class of 1891 portrait, Galter Library Special Collections.

In 1891 Curtis earned his MD from Northwestern and became the first intern to serve at the newly opened Provident Hospital. He became the first Black physician to receive a staff appointment at a de facto white hospital when he was brought on as an attending surgeon at Cook County Hospital in 1896. While on staff at Provident and Cook County, Curtis maintained a private surgical practice. He became a highly respected surgeon due to the abundant and varied training he received while working at the hospitals and his mentorship under Daniel Hale Williams, an accomplished and renowned Chicago surgeon. Curtis followed in Williams’ footsteps when he succeeded Williams in the position of Surgeon-in-Chief at Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington, DC. Image at left: Curtis' medical school Class of 1891 portrait, Galter Library Special Collections.

Curtis led Freedmen’s for four years, at which point he stepped down to focus on his private practice and his faculty position at Howard University Medical School (Freedmen’s was the teaching hospital for Howard). He rose in the ranks at Howard becoming the first Black chair and fourth chair ever of the Department of Surgery in 1928. Curtis held this position for eight years, steering the department through the worst of the Great Depression. He served as a faculty member at Howard for 40 years.

In addition to his skill as a surgeon, Curtis left a legacy in his role as an educator. At Howard, he was highly regarded for his clinical instruction, particularly because he demonstrated to students how important attention to detail and keen observation were to surgical success. At a time when imaging was still in its infancy and hospital laboratories did not yet offer many diagnostic tests, observation and detailed medical history were paramount for accurate diagnoses, and thus successful operations. Curtis' educational reach extended beyond Howard when he became one of the earliest participants in the surgical clinics that took place during the annual meetings of the National Medical Association, the first professional organization to serve Black physicians in the US (the American Medical Association was racially segregated at the time). These clinics “offered Section members the opportunity to develop cognitive and motor skills in surgical diagnosis and operative techniques under the supervision of leading black surgeons.”1

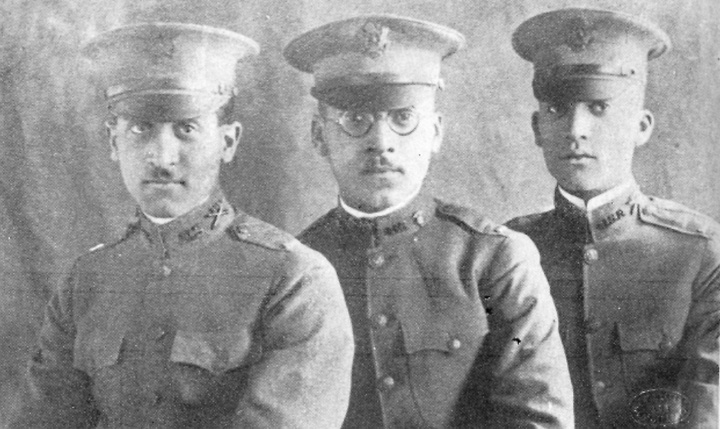

Austin and Namah Curtis had three sons and a daughter who were prominent and active community members in both Chicago and Washington. Austin participated in a variety of civic clubs and leagues, and Namah—in addition to her roles as wife and mother—was involved in relief work, public service, activism, and politics. When the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898, yellow fever began to spread rampantly in the US encampments. Because of her organizing skills and political insight, Namah was tapped to recruit and lead Black women who, like her, had recovered from yellow fever and were considered fully immune, to serve as contract nurses in Cuba. Namah was recognized for her service with a high commendation, a lifelong government pension, and burial in Arlington National Cemetery. These efforts contributed to the long process of acceptance of women nurses in the armed forces.  The Curtises' sons followed in their father's stead by becoming physicians (all trained at Howard no less), and their mother's by serving as commissioned officers in World War I. Curtis opened a private surgical hospital and his oldest son, Arthur, to provide the Black community in Washington, DC, with a healthcare option other than home care or Freedmen's. Image at right: A. Maurice Curtis, Medical Reserve Corps; Arthur L. Curtis, 368th Medical Corps; Merrill H. Curtis, 349th Field Artillery, all First Lieutenants, from Scott's Official History of the American Negro in the World War, by Emmett J. Scott.

The Curtises' sons followed in their father's stead by becoming physicians (all trained at Howard no less), and their mother's by serving as commissioned officers in World War I. Curtis opened a private surgical hospital and his oldest son, Arthur, to provide the Black community in Washington, DC, with a healthcare option other than home care or Freedmen's. Image at right: A. Maurice Curtis, Medical Reserve Corps; Arthur L. Curtis, 368th Medical Corps; Merrill H. Curtis, 349th Field Artillery, all First Lieutenants, from Scott's Official History of the American Negro in the World War, by Emmett J. Scott.

Austin Curtis passed away in 1939 in Washington, DC, leaving behind an indelible influence on American medicine. He impacted thousands of lives—from the patients he treated to the students he taught—and he played a crucial role in building healthcare infrastructure for communities deliberately left out by the medical establishment.

Endnotes

1. Matory, in A Century of Black Surgeons, 460.

Selected References

Cobb, W. Montague. "Medical History: Austin Maurice Curtis, 1868-1939." Journal of the National Medical Association 46, no. 4 (July 1954): 294-298. PMCID: PMC2617381.

Neumann, Caryn. "Curtis, Namahyoke Sockum." Oxford African American studies center. 31 May 2013. Accessed 10 Jan 2022. https://doi.org/10.1093/acref/9780195301731.013.38346.

Organ, Claude H. and Margaret M. Kosiba, eds. A Century of Black Surgeons: The U.S.A. Experience. 2 vol. Norman, OK: Transcript Press, 1987.

Updated: February 23, 2022