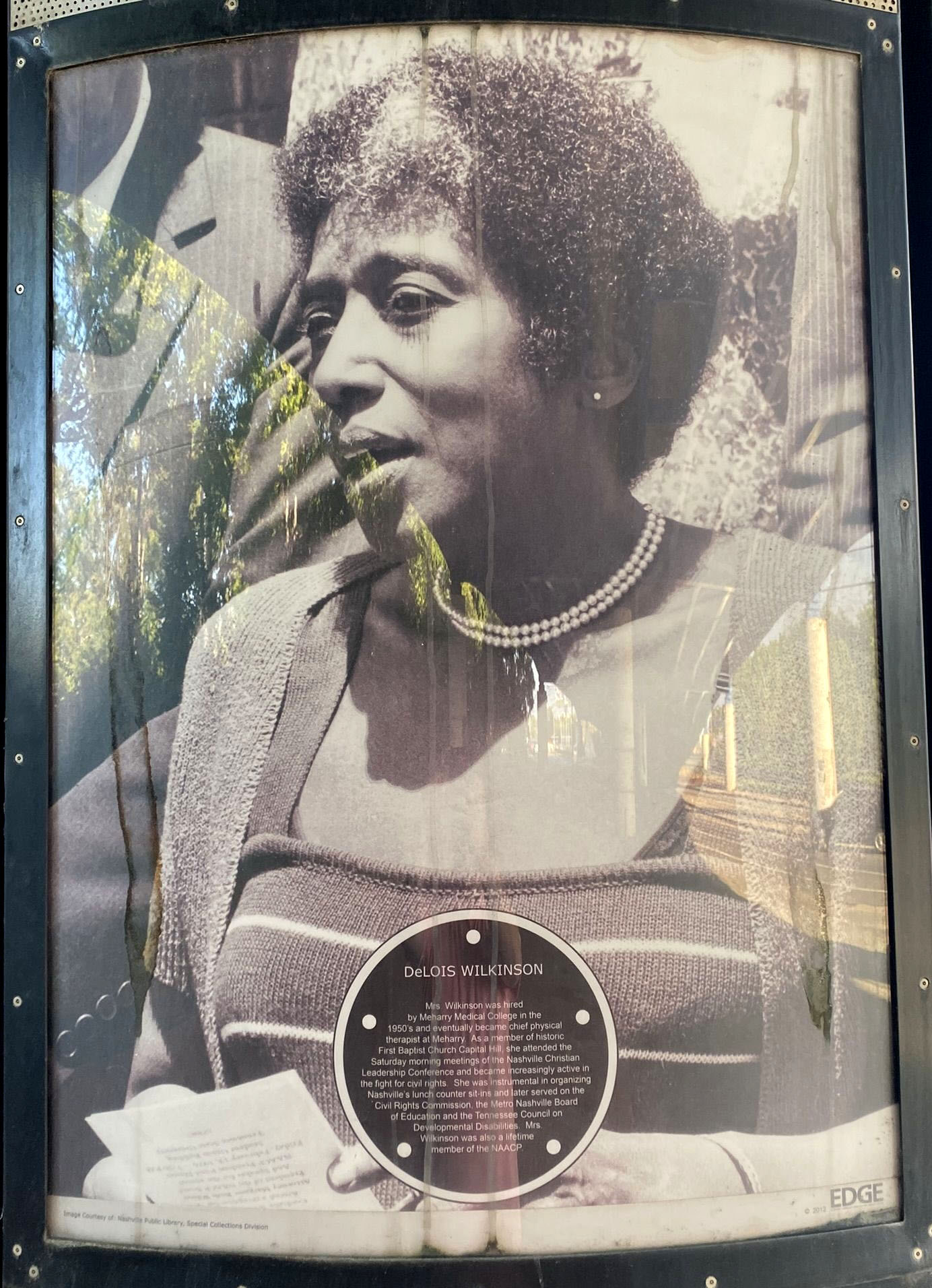

DeLois Jackson Wilkinson, BS, PT, 1924-2005

By Emma Florio, Archives & Research Specialist

|

|

Wilkinson, circa 1946, from the Records of the Department of Physical Therapy and Human Movement Sciences, Galter Library Special Collections

|

DeLois Jackson was born on May 12, 1924, in a suburb of Memphis, Tennessee, and was raised as one of 8 children in Helena, Arkansas. She earned a BS in biology from Memphis’s LeMoyne College before entering Northwestern University Medical School’s Physical Therapy program in October 1945.¹ Following her graduation one year later, she joined the staff of Chicago’s Provident Hospital, where her fellow Northwestern PT alumna Thelma Brown Pendleton had recently started the PT department. After two years at Provident, she moved to Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington, D.C., now Howard University Hospital.

By the early 1950s, Jackson had returned to Tennessee and married Fred Wilkinson, with whom she would have 5 children. Around this time, she was hired by Nashville’s Meharry Medical College—one of the first historically Black medical schools in the country—to set up a physical therapy department. This was the first time the Black community of the area had access to physical therapy care. One prominent patient was future Olympian Wilma Rudolph. Unable to find adequate care after she contracted polio, her parents traveled 50 miles to bring her to Meharry, where Wilkinson treated her. Rudolph would go on to become a world-famous sprinter, winning a bronze medal at the 1956 Summer Olympics and three gold medals in 1960. In 1962, Wilkinson was hired by the new Park Vista Convalescent Hospital and Nursing Home to establish a physical therapy department. She also used her physical therapy expertise in Nashville’s schools for disabled children, focusing her work especially on children with cerebral palsy.

|

|

Historical marker in honor of Wilkinson, in downtown Nashville, installed ca. 2012. Via HMdb.org

|

While she was busy establishing herself as a pioneering physical therapist in Nashville, Wilkinson was also becoming one of the city’s leading civil rights activists. Her membership of the First Baptist Church, Capitol Hill, where leading nonviolence strategist James Lawson led workshops on civil disobedience, brought her into contact with student leaders such as future US Representative John Lewis. Alongside these students, she organized sit-ins at Nashville’s segregated lunch counters. She also participated in the 1963 March on Washington and the 1983 20th Anniversary March. Because of these and many more activities, she was known as “Miss Civil Rights” in Nashville.

Wilkinson’s later life included many forays into local politics. She ran for Tennessee State Representative in 1980 and the city’s Metro Board of Education in 1982, for which she had been recommended by the mayor. She served as a Democratic Executive Committee member in Nashville’s government as well as a delegate to the 1978 Democratic National Convention. She was also a member of the Tennessee Federation of Democratic Women, the Civil Rights Commission, and the Tennessee Council on Developmental Disabilities.

DeLois Jackson Wilkinson died on January 30, 2005, in Nashville. Reflecting her prominence in Tennessee, US Representative Jim Cooper celebrated her life on the floor of the US Congress, remarking that, upon her death, “our country lost a dedicated advocate and a dear friend.” She is buried in Nashville, under a tombstone that reads “May the works I’ve done speak for me.”

Endnotes

1. The first Black students had been admitted to the program only 3 months earlier. Read about the struggle to integrate the program, and one of its first students, Thelma Brown Pendleton, here.

Selected References

Lewis, Dwight. “DeLois Wilkinson, ‘Miss Civil Rights’ who assisted sit-ins, dies after stroke.” The Tennessean (Nashville, TN), Feb. 1, 2005.

“Our Approach.” Wilkinson Health Management. Accessed February 25, 2025.

Updated: February 27, 2025