Celebrating Black History

Throughout February, Galter Library will be participating in Black History Month by sharing short biographies of Black graduates and faculty from Northwestern’s past. We join institutions across the United States in recognizing the achievements and contributions of Black Americans to our society and culture, while also acknowledging the oppressive role our institution has played, both locally and as part of a societal system, in prejudice and discrimination against Black Americans.

Content Warning: this article includes a mention of suicide, as well as outdated, offensive terms and views.

James E. Henderson, MD, ca. 1858-1918

By: Emma Florio, Special Collections Library Assistant

Daniel Hale Williams is deservedly prominent in the history of Black students at Chicago Medical College, the predecessor of Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. In recent years, he has often been referred to as the first Black graduate of the medical school. But there was another Black student in his graduating class of 1883: James Edward Henderson.¹ Williams’s achievements—as one of the founders of Chicago’s Provident Hospital, the country’s first African American owned and operated hospital, and the surgeon who performed the first documented successful pericardium surgery in the United States—cause him to loom large in Northwestern’s history, perhaps overshadowing others who should rightfully be included in the discussion of the early history of Black students at the school, including Henderson.

J ames Henderson was born sometime around 1858 in Nashville. By the 1870s he had come to Chicago and enrolled at the University of Chicago, appearing in the University’s catalog as a freshman in 1875. During his time as a student, he helped found the Chicago Conservator, the city’s first African American newspaper, which published its first issue on January 1, 1878. Sometime after graduating from Chicago Medical College in 1883 Henderson moved to Kansas City, Missouri, before settling in Springfield, Illinois, in the mid-1890s. Image at left: Henderson’s Chicago Medical College Class of 1883 portrait, Galter Library Special Collections.

ames Henderson was born sometime around 1858 in Nashville. By the 1870s he had come to Chicago and enrolled at the University of Chicago, appearing in the University’s catalog as a freshman in 1875. During his time as a student, he helped found the Chicago Conservator, the city’s first African American newspaper, which published its first issue on January 1, 1878. Sometime after graduating from Chicago Medical College in 1883 Henderson moved to Kansas City, Missouri, before settling in Springfield, Illinois, in the mid-1890s. Image at left: Henderson’s Chicago Medical College Class of 1883 portrait, Galter Library Special Collections.

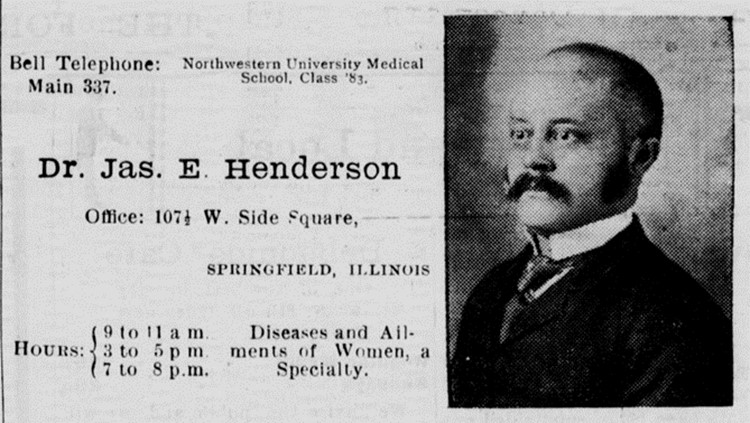

It is clear from Springfield newspapers that Henderson was a successful physician and a prominent member of the city’s Black community. His name appears dozens of times in the Forum, a leading African American newspaper in Springfield, including in short notices about ill people under his care and in longer editorials praising his character and his skills as a physician. An editorial from October 5, 1907, states “there is not a man in the city, of any race, possessing more thorough education, a higher moral standing, more efficient [sic] as a physician or a better integrity” and that “we, as a part of Springfield’s citizenry, are proud that we possess men of his calibre [sic].”² In September 1916, his purchase of an automobile warranted a short notice in the paper; a week later, a longer notice explained he had “one of the most substantial auto [sic] in the city, a very convenient asset to his business,” and referred to him as “among the few ablest physicians in the city.”³ A particularly noteworthy notice in the Forum on November 16, 1907, explains that Henderson “received an urgent request for medical services this week from far distant Capetown, Africa [sic].”⁴ It is not clear if Henderson did travel to South Africa—though it seems unlikely to have happened without a mention in the Forum—but the fact that his reputation had reached other continents speaks volumes. Image at right: Advertisement for Henderson’s practice that appeared in the Forum newspaper on September 14, 1907.

“among the few ablest physicians in the city.”³ A particularly noteworthy notice in the Forum on November 16, 1907, explains that Henderson “received an urgent request for medical services this week from far distant Capetown, Africa [sic].”⁴ It is not clear if Henderson did travel to South Africa—though it seems unlikely to have happened without a mention in the Forum—but the fact that his reputation had reached other continents speaks volumes. Image at right: Advertisement for Henderson’s practice that appeared in the Forum newspaper on September 14, 1907.

Henderson was also heavily involved in the community beyond his work as a physician. In 1902 he ran as an independent candidate for a seat in the Illinois House of Representatives. Although he did not win, he remained active in Springfield’s political, cultural, and religious circles. Throughout the first decades of the 20th century, Henderson made speeches on the subject of race at a variety of meetings in the city. According to the Forum, he made a speech called “Comparative Race Ability” at St. Paul’s African Methodist Episcopal Church in February 1917 which addressed the cultural and then-accepted pseudoscientific notions of differences among races. In the speech, he discussed how “the Negroes [sic] mental, moral, intellectual and ethical endowments are constantly call [sic] into question” and went on to refute this idea.⁵ These speeches and other events in Henderson’s life contributed to a racist perception of him that led the Illinois State Register to describe him in his obituary as having been “notorious as a ‘fanatic’ on the subject of race prejudice.”⁶

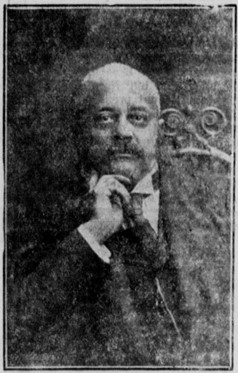

Despite his apparent success in earlier years, the end of Henderson’s life was marked by difficulties and tragedy. When the United States entered the First World War in 1916, Henderson’s advocacy for his fellow African Americans came under the scrutiny of the federal government. In June 1917 Congress enacted the Espionage Act, prohibiting interference with military operations or recruitment. Two years earlier, Henderson had begun issuing an anonymous inflammatory pamphlet that described itself as a  “FIRST SHOT in the initial skirmish, inaugurating a War of Races unless colored people are treated better.” After the United States entered the war, Henderson increased his distribution of the pamphlet, and it was brought to the attention of the relatively new Bureau of Investigation, which traced it back to him. He was arrested on September 19, 1917, and charged with attempting to incite race riots and interfering with the recruitment of Black troops. Although he was not prosecuted, the persecution and damage done to his reputation left him despondent, according to an Illinois State Register article published after his death. Image at left: Portrait of Henderson from a later Forum advertisement in 1916.

“FIRST SHOT in the initial skirmish, inaugurating a War of Races unless colored people are treated better.” After the United States entered the war, Henderson increased his distribution of the pamphlet, and it was brought to the attention of the relatively new Bureau of Investigation, which traced it back to him. He was arrested on September 19, 1917, and charged with attempting to incite race riots and interfering with the recruitment of Black troops. Although he was not prosecuted, the persecution and damage done to his reputation left him despondent, according to an Illinois State Register article published after his death. Image at left: Portrait of Henderson from a later Forum advertisement in 1916.

James Edward Henderson died by suicide sometime in early April 1918, leaving a note that described his actions as “the culmination of more than twenty years of trouble and persecution in which I am by no means blameless—a fitting climax to the life I have led.”⁷ While he did experience trouble and persecution, especially toward the end of his life, the numerous positive mentions Henderson received in the Forum and elsewhere demonstrate his success as a physician and his importance in Springfield; he diligently tended to and advocated for his community, a fitting legacy for a man who can claim an important spot in the history of Black graduates of the medical school.

Endnotes

1. In fact, Williams and Henderson may not even be the first Black students at Chicago Medical College. There may have been one or two students of color who attended during the 1868-69 academic year. Special Collections staff are currently researching these men and their connection to Northwestern, and we plan to share our findings at a later date.

2. “Editorial,” Forum (Springfield, IL), Oct. 5, 1907.

3. Forum, Sept. 9, 1916.

4. “Services Wanted in South Africa,” Forum, Nov. 16, 1907.

5. “Services at St. Paul A. M. E. Church,” Forum, Feb. 10, 1917.

6. “Negro Doctor Takes Own Life,” Illinois State Register (Springfield, IL), April 12, 1918.

7. Ibid.

Selected References

Ellis, Mark. Race, War, and Surveillance: African Americans and the United States Government during World War I. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001.

Forum, Springfield, Illinois.

Illinois State Register, Springfield, Illinois.

Updated: February 16, 2022