James P. Carter, MD, DPH (1933-2014)

By Emma Florio, Archives & Research Specialist

|

|

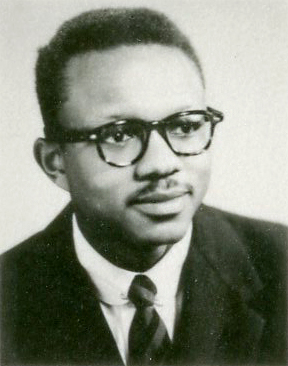

Carter’s medical school class of 1957 portrait. From Galter Special Collections.

|

James Puckette Carter was born on October 7, 1933, in Chicago, Illinois. Although his father was a physician with his own private practice, Carter had initially wanted to be a musician. By the time he was a senior at Chicago’s Englewood High School, though, his ambition had shifted to becoming an expert surgeon. In 1954, he earned a BS in chemistry from Northwestern University and then enrolled at Northwestern University Medical School, as the only Black student in his graduating class.

After earning his MD from Northwestern in 1957, Carter’s turned his focus to nutrition and pediatrics. When asked later in life why he chose not to go into private practice like his father, Carter observed that second generation doctors often went into academic medicine or public health, which is exactly what he did (years later, he would eventually open his own private clinic). He earned an MS in parasitology from Columbia School of Public Health in 1963 and a Doctor of Public Health in nutrition from the same institution in 1966. During this time, he married Gena Hunter, a Chicago schoolteacher and Nashville native, with whom he would have three children. In 1967 he was hired as the first Black faculty member in Vanderbilt University School of Medicine’s Department of Pediatrics, and the medical school's first full-time Black faculty member. He taught there for the next 9 years.

Through the late 1960s and early ‘70s, Carter became a leading and sought-after expert in malnutrition and hunger in underserved populations in the United States and Africa. He traveled throughout the world as a lecturer and physician. In partnership with Meharry Medical College, a historically Black college only 2 miles away from Vanderbilt in Nashville, Carter helped train health professionals in developing African nations. Closer to home, he studied hunger and malnutrition in Tennessee and South Carolina, the latter of which led South Dakota Senator and future presidential candidate George McGovern to urge immediate federal food distribution in rural South Carolina. Carter also served as a consultant in nutrition to the World Health Organization and the United States Agency for International Development. His activism extended beyond medicine—in 1969 he co-curated an exhibit of photographs depicting poverty and hunger in America, displayed in Vanderbilt’s main chapel. The exhibit, along with an accompanying book, gained national attention.

|

|

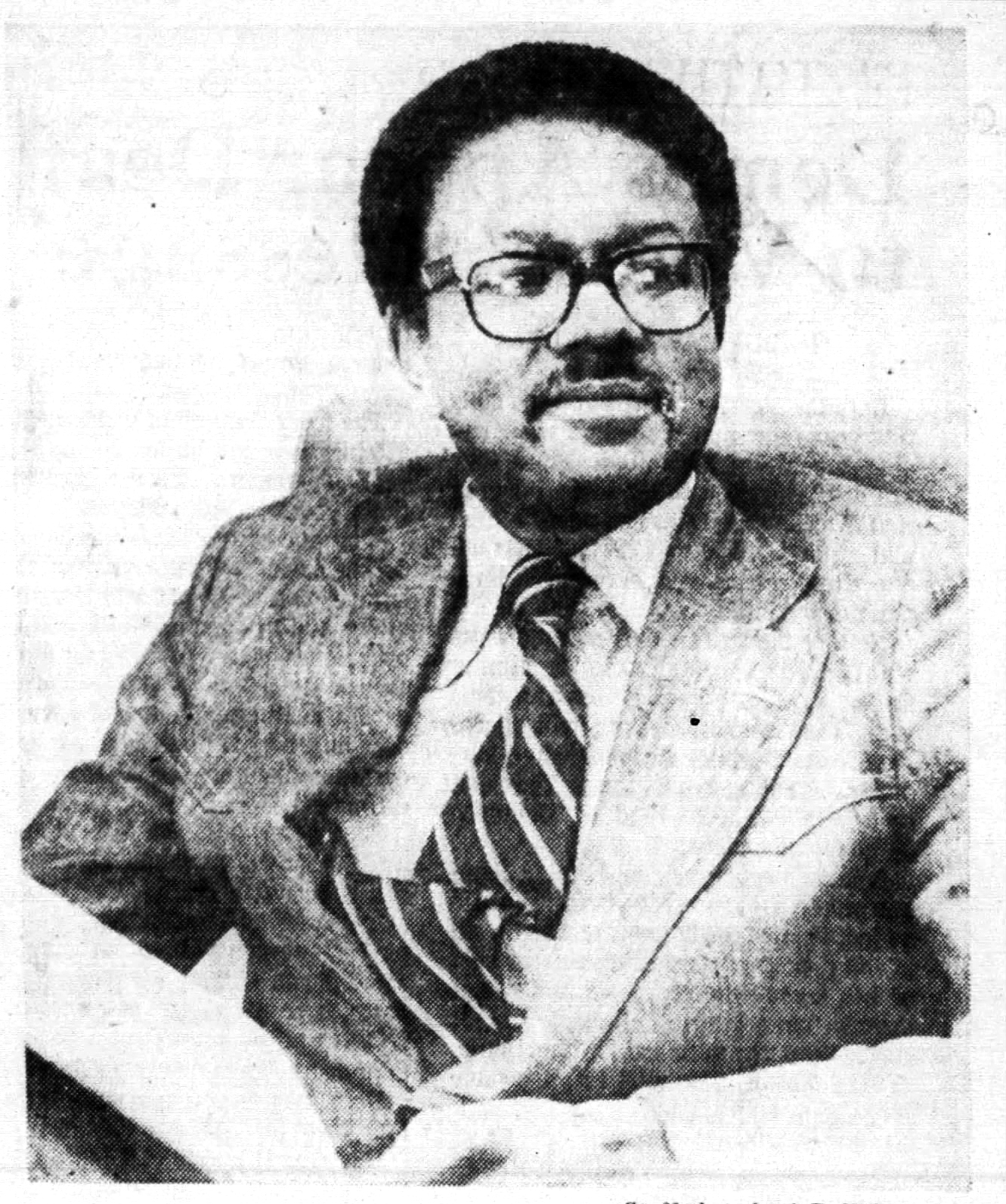

Carter later in life, from the New Orleans Times-Picayune, August 5, 1976.

|

In 1976, Carter was hired by Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine in New Orleans as chair of the Department of Nutrition, as well as a clinical professor of pediatrics. He continued to work at Tulane for over 25 years. In the latter part of his career, he became more outspoken about his views related to medicine and the problem of hunger in the country. In his first years at Tulane, he expressed the need for more Black health professionals in all categories and he criticized governmental food programs for being uncoordinated and fragmented and thus not getting food to the people who needed it most.

In the middle of his career, Carter became interested in complementary and alternative medicine. He advocated for and performed a number of treatments that were not approved by mainstream medicine, including EDTA chelation therapy for cardiovascular health (a non-FDA approved use of the therapy), colonic irrigation for general detoxification, vegan and macrobiotic diets to treat cancer, and the use of evening primrose oil for various conditions (an approved treatment in many European countries, but not the United States). He was investigated multiple times in the 1980s by State Boards of Medical Examiners for his use of alternative treatments and ties to companies that marketed them, accusing him of efforts to deceive or defraud the public, medical incompetency, and unprofessional conduct. The investigations were dismissed, perhaps partially due to his long academic record and position at a major research institution. These experiences led him to publish a book called Racketeering in Medicine: The Suppression of Alternatives in 1993, which claimed to expose evidence that alternative and natural therapies were being suppressed by organized medicine for political and financial reasons. For example, he stated evening primrose oil was suppressed because it relieved problems that formed the market for aspirin and cholesterol drugs.

In 2005, both Carter’s home and medical office were destroyed by flooding and subsequent fires following Hurricane Katrina. He moved to Mandeville, a city across Lake Pontchartrain from New Orleans, and quickly reestablished his private practice with a focus on integrative medicine. He continued research, clinical trials, and private clinic work related to alternative medicines until his death in 2014. Five years after his death, the Louisiana State Senate adopted a resolution posthumously commending Carter “for his historic contributions in the fields of medicine and nutrition,” noting he strove “for fulfillment of a passion to make the world a better place.”

Selected References

Carter, James P. Racketeering in Medicine: The Suppression of Alternatives. Norfolk, VA: Hampton Roads Publishing Company, 1993.

Commendations. Posthumously commends James Puckette Carter, MD for his historic contributions in the fields of medicine and nutrition. Louisiana SR NO. 201. 2019 Regular Session.

Haynes, Valerie M. “Stint in Africa Behind TU Nutritionist.” The Times-Picayune (New Orleans), August 5, 1976.

Updated: February 11, 2026