Warren F. Spencer, MD, 1921-1987

By Emma Florio, Special Collections Library Assistant

Warren Frank Spencer was born in Chicago on September 29, 1921, to Evanston residents John J. Spencer, a Pullman porter, and Osceola Outlaw Spencer, a teacher who would go on to attend nursing school in her 70s. He graduated from Evanston Township High School in 1939 and attended Lincoln University, a historically Black university in Jefferson City, Missouri. He enlisted in the Army in 1943 and remained in Europe after his military service, studying at the University of Florence for a time before returning to Evanston in 1947. In 1953 he married Mayme Finley, a histology lab technician at Mt. Sinai Hospital who would later earn a law degree from the Chicago-Kent College of Law. They would have four daughters together. Image at right: Spencer's medical school class of 1955 portrait, Galter Library Special Collections.

Warren Frank Spencer was born in Chicago on September 29, 1921, to Evanston residents John J. Spencer, a Pullman porter, and Osceola Outlaw Spencer, a teacher who would go on to attend nursing school in her 70s. He graduated from Evanston Township High School in 1939 and attended Lincoln University, a historically Black university in Jefferson City, Missouri. He enlisted in the Army in 1943 and remained in Europe after his military service, studying at the University of Florence for a time before returning to Evanston in 1947. In 1953 he married Mayme Finley, a histology lab technician at Mt. Sinai Hospital who would later earn a law degree from the Chicago-Kent College of Law. They would have four daughters together. Image at right: Spencer's medical school class of 1955 portrait, Galter Library Special Collections.

In 1955, Spencer earned his MD from Northwestern University Medical School and by 1957 he had established his own practice in Evanston as a general practitioner.¹ He later joined the staff of St. Francis Hospital, which he helped to integrate in the 1960s, and Evanston Community Hospital, where he would later become chief of staff. He also worked at Bethesda Hospital in the Rogers Park neighborhood of Chicago. Spencer, who was called “Doc” by people who knew him, was an advocate for racial equity in neighborhood health centers and in medical and nursing schools.² He was involved in the wider medical community as an officer of the Cook County Physicians’ Association, which represented Black physicians. Later in his career he researched diet and anorexia nervosa among Black women and was featured in Jet magazine for this research multiple times.³

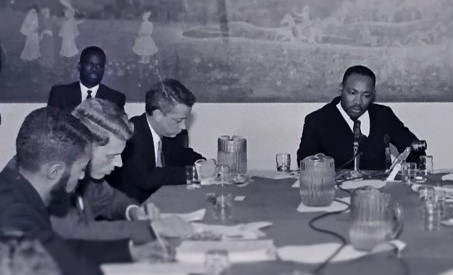

Beyond medicine, both Spencer and his wife, Mayme were involved in politics and the Civil Rights movement in Evanston. He was president of the Evanston branch of the NAACP from 1957 to 1963 and led other civil rights efforts along the North Shore, such as organizing interracial picnics in the northern suburbs with the Suburban Human Relations Council and staging sit-ins to protest racist housing practices in Evanston. Mayme earned her law degree in 1961 and joined the Evanston law firm Stewart and May, whose offices were in the same building as her husband’s medical practice. In 1963 she became the first Black female alderperson in Evanston and served two terms representing the 5th ward. Committed to the continuing efforts of desegregation, Mayme used her platform to campaign for open housing and Spencer served on the board of HOME (Home Opportunities Made Equal), a group that encouraged Black people to move into all-white communities along the North Shore. Image at left: Spencer (in background on left) with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., at a press conference at the Orrington Hotel in Evanston, October, 1962. Photo by Evanston Photographic Studio, courtesy of Shorefront.

Beyond medicine, both Spencer and his wife, Mayme were involved in politics and the Civil Rights movement in Evanston. He was president of the Evanston branch of the NAACP from 1957 to 1963 and led other civil rights efforts along the North Shore, such as organizing interracial picnics in the northern suburbs with the Suburban Human Relations Council and staging sit-ins to protest racist housing practices in Evanston. Mayme earned her law degree in 1961 and joined the Evanston law firm Stewart and May, whose offices were in the same building as her husband’s medical practice. In 1963 she became the first Black female alderperson in Evanston and served two terms representing the 5th ward. Committed to the continuing efforts of desegregation, Mayme used her platform to campaign for open housing and Spencer served on the board of HOME (Home Opportunities Made Equal), a group that encouraged Black people to move into all-white communities along the North Shore. Image at left: Spencer (in background on left) with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., at a press conference at the Orrington Hotel in Evanston, October, 1962. Photo by Evanston Photographic Studio, courtesy of Shorefront.

Warren Frank Spencer died at St. Francis Hospital in Evanston on November 9, 1987, leaving a legacy of dedication to health equity and civil rights, and survived by his wife. After her death in 2011, Mayme was recognized by the Evanston City Council as a key figure in bringing about the city’s open-housing ordinance in 1968. Just over 5 years ago, Spencer was honored posthumously with a Distinguished Alumni Award by Evanston Township High School in 2018. Warren and Mayme Spencer are remembered as pioneering activists who consistently advocated for racial equity and integration and had a significant impact on the rights and the future of the Black community in Evanston.

Endnotes

1. Spencer was one of only two Black students in his graduating class, the other being Allen N. Levy, Jr. Although a number of Black men had graduated from NUMS and its predecessor Chicago Medical College in the 19th and early 20th centuries, there appear to have been no Black graduates of NUMS from the late 1920s through the early 1950s.

2. A 1966 letter Spencer wrote on the subject of discrimination in healthcare was featured among the items in a National Library of Medicine digital exhibit on citizen action in healthcare reform.

3. “Diet Craze among Black Women May Be Slow Death” February 19, 1976; Words of the Week, March 18, 1976.

Selected References

Messenger, Janet G. “City’s First Black Woman Alderman, Mayme Spencer, Remembered as Open-Housing Advocate,” Evanston Round Table. February 15, 2011.

Prince, Jacqueline W. “Civic-Minded Citizens Build a New America,” Chicago Defender. April 22, 1967.

Updated: February 22, 2023