By: Ron Sims, Special Collections Librarian

This article was featured in Library Notes #48 (Fall 2008).

"What good is a book without pictures?" -- Alice

The current exhibit on the 2nd level atrium walkway of the Galter Health Sciences Library brings together images of the human brain. Nearly 500 years of study and scholarship are represented, from a medieval manuscript to an early 19th century hand colored aquatint copper engraving.

Based on Mondino dei Luzzi's text (d. 1326), Guido da Vigevano provided the earliest representations of human anatomy and the brain in a manuscript from about 1345.

Based on Mondino dei Luzzi's text (d. 1326), Guido da Vigevano provided the earliest representations of human anatomy and the brain in a manuscript from about 1345.

From Leonardo da Vinci's Anatomical studies (ca. 1490), a fine example of his genius is displayed in facsimile. Gregor Reisch's Margarita philosophica (1504) woodcut profile of the head illustrates his three "cerebral cells" or ventricles. According to Reisch the frontal cavity was the site of perception, fantasy and imagination; middle cavity, the site of thought and judgment; posterior cavity, the site of memory.

Johann Dryander's image from Anatomia Mundini (1541) shows the meninges having been pulled aside to reveal the cerebral convolutions. Like the Guido da Vigevano manuscript, Dryander's text is also based on editions of Mondino.

Andreas Vesalius, the father of modern anatomy, is represented by a 1568 edition of his De humani corporis fabrica, where three figures reveal the course of the middle meningeal artery over the dura, the calvarium and the meninges which have been removed to show the cerebral convolutions.

Thomas Willis' De cerebri anatome (1666), English physician and anatomist is best known for describing the arterial structure at base of the brain appropriately called "circle of Willis." While not the first to describe this structure, his description of the arteries of the brain was fuller and functionally more complete than any before it. His series of studies on brain anatomy, first published in 1664, is a milestone in the development of neuroscience. He is credited for the first modern images of central nervous system anatomy. The images were drawn by Christopher Wren.

Govard Bidloo in his Anatomia humani corporis (1685) portrays images in a total departure from the idealistic tradition created by Vesalius. The figures display everyday realism and sensuality, contrasting the raw dissected parts of the body with the full, soft surfaces of flesh surrounding them. The qualities of Dutch still-life painting are evident, giving a new, darker expression to the significance of dissection.

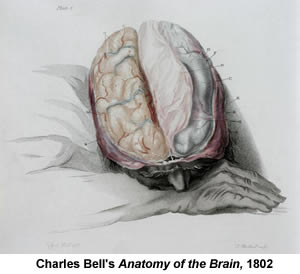

Other great anatomical images from Vesling (1677), Caspar Bartholin (1641), Vieussens (1685), Ridley (1695), Santorini (1775), Soemmerring (1778), Vicq-d'Azyr (1789) round out the exhibit, concluding with Charles Bell's Anatomy of the brain, explained in a series of engravings (1802).

Bell was a pioneer in the study of the human nervous system. While his fame rests mainly on medical illustration and neurology, he is also remembered for his description of the long thoracic nerve or "Bell's nerve"; his discovery that a lesion of the seventh facial nerve causes facial paralysis, known as "Bell's palsy"; and his demonstration of function in the spinal nerves, that motor function relates to anterior roots and sensory function relates to dorsal roots, the "Bell-Magendie law."

Bell was a pioneer in the study of the human nervous system. While his fame rests mainly on medical illustration and neurology, he is also remembered for his description of the long thoracic nerve or "Bell's nerve"; his discovery that a lesion of the seventh facial nerve causes facial paralysis, known as "Bell's palsy"; and his demonstration of function in the spinal nerves, that motor function relates to anterior roots and sensory function relates to dorsal roots, the "Bell-Magendie law."

In his Advertisement at the beginning of his 1802 text, Bell states,

In the Brain the appearance is so peculiar and so little capable of illustration from other parts of the body, the surfaces are so soft, and so easily destroyed by rude dissection, and it is so difficult to follow an abstract description merely, that this part of Anatomy cannot be studied without the help of Engravings.

This text vividly shows both the descriptive and artistic abilities of Bell.

The 2nd level exhibit is ongoing, so please take a moment to savor these treasures on your next visit to the Galter Library.

Updated: September 24, 2023