By: Galter Staff

Content Warning: this article includes mention of historical offensive and racist views.

Mary Elizabeth Bates was born on February 25, 1861, in Manitowoc, Wisconsin to William Wallace Bates and Mary Bates (nee Cole). In her pursuit of medicine, Bates took after her mother, who studied at the New York City Hydropathic Medical School. Raised in Chicago, she would go on to study medicine at the Woman’s Medical College of Chicago, later called the Northwestern University Woman’s Medical School. At the age of 20, she completed her degree in February 1881 and the following month received an internship, making her the first woman intern at Cook County Hospital in Chicago.1 Enduring months of opposition, hazing, and discouragement by her male colleagues and superiors, Bates graduated from her internship in October of 1882. Image at Left: Mary Elizabeth Bates, Cook County Hospital, circa 1881.

Mary Elizabeth Bates was born on February 25, 1861, in Manitowoc, Wisconsin to William Wallace Bates and Mary Bates (nee Cole). In her pursuit of medicine, Bates took after her mother, who studied at the New York City Hydropathic Medical School. Raised in Chicago, she would go on to study medicine at the Woman’s Medical College of Chicago, later called the Northwestern University Woman’s Medical School. At the age of 20, she completed her degree in February 1881 and the following month received an internship, making her the first woman intern at Cook County Hospital in Chicago.1 Enduring months of opposition, hazing, and discouragement by her male colleagues and superiors, Bates graduated from her internship in October of 1882. Image at Left: Mary Elizabeth Bates, Cook County Hospital, circa 1881.

Following her graduation, Bates became a professor of anatomy at the Woman’s Medical College and eventually served as the chair of the department. She was a mentor to students and guided them in securing their own medical internships at Cook County Hospital. In October of 1890, Bates relocated to Denver and continued her advocacy work there. In addition to working to give women physicians the right to hold internships at Arapahoe County Hospital, Bates was also active in the Colorado Equal Suffrage Association and worked to secure the vote for women in Colorado in 1893.

Outside of her medical practice, Bates volunteered for many organizations and movements that aimed to shape American society. She advocated for public health measures like cleaner cities and safe public drinking fountains, and she was passionate about the humane treatment of animals. In addition to her work throughout the women’s suffrage movement, Bates called for more attention to be paid to elder care and children’s health and welfare. She played a significant role in creating early consent laws to protect the rights of women and children. Bates served as a board member for various groups and organizations, from her roles as a secretary for the Colorado Humane Society to vice president of the first woman’s Political Club of Colorado.

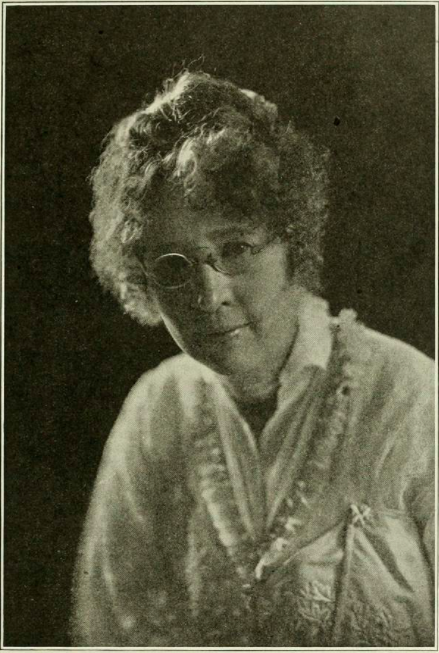

She continued her advocacy and political interests throughout her life. As the secretary of the Colorado Medical Women’s War Service, Bates fought to have female physicians recognized as equal to male physicians in opportunity, rank, and pay during World War I. She was also an active member of the animal advocacy group called the Denver Dumb Friends League. After she retired, she volunteered for local humane societies and her activism culminated in the Mary Elizabeth Bates Foundation, established shortly before her death in 1954, which provided funds for the care of animals. Image at right: Mary Elizabeth Bates from History of Colorado, 1918.

She continued her advocacy and political interests throughout her life. As the secretary of the Colorado Medical Women’s War Service, Bates fought to have female physicians recognized as equal to male physicians in opportunity, rank, and pay during World War I. She was also an active member of the animal advocacy group called the Denver Dumb Friends League. After she retired, she volunteered for local humane societies and her activism culminated in the Mary Elizabeth Bates Foundation, established shortly before her death in 1954, which provided funds for the care of animals. Image at right: Mary Elizabeth Bates from History of Colorado, 1918.

It is important to note that Bates played an active role in the eugenics movement, a movement rooted in racist, xenophobic, and ableist views. The eugenicist worldview was not uncommon in the medical establishment in the early 20th century, and led to deeply harmful and traumatic actions and practices. Starting in 1913, Bates introduced the “Baby Health Contest” to Denver. Mothers would enter their young children into this prize competition, first held at an Iowa stock show, and local doctors and nurses would assess the children based on the score card criteria. Bates helped develop the score card, and even served as vice president of the National Eugenic Society, an organization formed specifically to bring the contest to county fairs and stock shows around the country. Participants rationalized these contests because they were promoted as “scientific,” but often the goal was to promote the bodies of non-immigrant, able-bodied white children and their mothers.

Footnotes

1. Internships at Cook County Hospital were considered some of the best opportunities for practical education in medicine and surgery. Women were first allowed to compete for these positions in 1879. Marie Mergler, that year's valedictorian of the Woman's Medical College, earned the highest marks and thus secured an appointment at the Cook County Insane Asylum. She was ultimately denied the position as it was deemed unsuitable for a woman.

References

Jensen, Kimberly. “The ‘Open Way of Opportunity’: Colorado Women Physicians and World War I.” The Western Historical Quarterly 27, no. 3 (1996): 327–48. https://doi.org/10.2307/970143.

Stone, Wilbur Fiske. History of Colorado. Vol. 2. United States: S. J. Clarke, 1918, 452, 454-457.

Updated: March 21, 2022