By: Ron Sims, Special Collections Librarian

In late December 2010, the Galter Library was pleased to accept donated materials from Barbara Miller, the great granddaughter of J. B. Murphy. Among the treasures are photographs, newspaper clippings, an oil portrait and copies of Dr. Murphy’s Clinics. One of the more interesting items is a letter of introduction dated January 5, 1891, addressed to German authorities in Berlin from the Cook County Hospital administration, requesting assistance in obtaining “Koch lymph” for the Hospital.

These and other items will be on display in the Eckenhoff Reference Room and the second level reception area of Special Collections through early fall 2011.

John Benjamin Murphy, MD, LLD, MSc was Professor of surgery at Northwestern from 1901 to 1905. Following a brief hiatus at the University of Illinois College of Medicine, he returned to Northwestern in 1908. He was chief of surgery at Mercy Hospital, Northwestern’s first teaching hospital, from 1895 until his death in 1916.

John Benjamin Murphy, MD, LLD, MSc was Professor of surgery at Northwestern from 1901 to 1905. Following a brief hiatus at the University of Illinois College of Medicine, he returned to Northwestern in 1908. He was chief of surgery at Mercy Hospital, Northwestern’s first teaching hospital, from 1895 until his death in 1916.

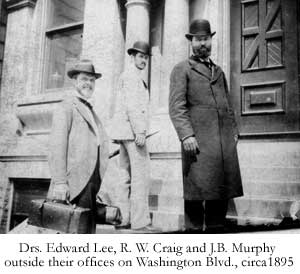

Born in a log cabin near Appleton, Wisconsin in 1857, John Murphy was to become an American surgical marvel of national and international fame. After attending a country grade school, he continued his education in Appleton, where a recent graduate of the University of Wisconsin, R. H. Schmidt, taught him logic and chemistry. Mr. Schmidt was a forceful speaker and was a great influence on young John and his classmates. Dr. H. W. Reilly, the Murphy family physician, became one of young John’s heroes, as well as his preceptor in medicine. After completing his anatomical and physiological studies with Dr. Reilly, Murphy entered Rush Medical College in 1877 and graduated in 1879. Following an internship at Cook County Hospital, he became an associate of Dr. Edward W. Lee in private practice.

The new era of medicine arrived from Europe in mid-19th century with the discoveries of Robert Koch, Louis Pasteur, and the germ theory. Under the tutelage of Danish born Dr. Christian Fenger and his pathology studies, Dr. Murphy was eager to learn more. In September 1882, he traveled to Vienna, Heidelberg, and Berlin to study with Billroth, Arnold, and Schroeder before returning to Chicago in the spring of 1884 where he re-joined Dr. Lee in private practice.

The new era of medicine arrived from Europe in mid-19th century with the discoveries of Robert Koch, Louis Pasteur, and the germ theory. Under the tutelage of Danish born Dr. Christian Fenger and his pathology studies, Dr. Murphy was eager to learn more. In September 1882, he traveled to Vienna, Heidelberg, and Berlin to study with Billroth, Arnold, and Schroeder before returning to Chicago in the spring of 1884 where he re-joined Dr. Lee in private practice.

On May 4, 1886, the great Hay Market Riot erupted in Chicago and Dr. Murphy was called to help with emergency cases at Cook County Hospital. As a result of this event, he received considerable publicity with his name being mentioned daily in the press.

Dr. Murphy’s interest in surgery was piqued when he encountered a patient, admitted with a fractured limb, also suffering pain in the right lower abdomen. Dr. Murphy recognized the symptoms of acute appendicitis and quickly removed the diseased organ. Standard practice of the day recommended waiting for rupture. He delivered a paper before the Chicago Medical Society advocating early operation and holding the profession responsible if they failed to do so. His strong statements were critically received. This bold approach exemplified Dr. Murphy’s colorful, controversial, and creative personality.

No one more brilliantly embodied the role of the general surgeon than Dr. Murphy. In addition to the familiar operations in general surgery, such as appendicitis, appendiceal abscess, cholecystostomy, intestinal obstruction, mastectomy, and others, he described and performed innovative procedures in neurosurgery, orthopedics, gynecology, urology, plastic surgery, thoracic surgery, and vascular surgery. He is given credit for the first successful arterial anastomosis in a case of a bullet wound of the femoral artery. Away from general surgery, Dr. Murphy pioneered his own techniques of neurorrhaphy, arthroplasty, prostatectomy, nephrectomy, hysterectomy, bone grafting, thoracoplasty, and other procedures.

His relationships with colleagues and peers ranged from acrimony to exalted accolades. Early in his career he was refused membership in the Chicago Medical Society and the American Surgical Association because of his bold personal style. Later in his career he became President of the Chicago Medical Society, President of the American Medical Association, and a belated member of the American Surgical Association. He was a proponent in the founding of the American College of Surgeons (1913).

Dr. Murphy’s legendary texts, Surgical Clinics of John B. Murphy, were transcribed by his staff as he lectured during surgery. Surgical Clinics of North America and its kindred series of discipline clinics were born out of Dr. Murphy’s first publication of 1912.

With Northwestern notables E. Wyllys Andrews, MD (1881), Franklin Martin, MD (1880), Allen Kanavel, MD (1899) and Nicholas Senn, MD (1868), he founded the publication Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics, the predecessor of the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

Scarcely any of Murphy’s original surgical techniques have stood the test of time, but that does not diminish his luminary role on the American surgical scene of his day. His intellect brimmed over with new ideas, few of which would have withstood the scrutiny of a present-day institutional review board or a clinical trial. In contrast to his contemporary, William Stewart Halsted, of the new Johns Hopkins Medical School in the East, Murphy left no lasting legacy of student disciples to carry his teachings forward.

Scarcely any of Murphy’s original surgical techniques have stood the test of time, but that does not diminish his luminary role on the American surgical scene of his day. His intellect brimmed over with new ideas, few of which would have withstood the scrutiny of a present-day institutional review board or a clinical trial. In contrast to his contemporary, William Stewart Halsted, of the new Johns Hopkins Medical School in the East, Murphy left no lasting legacy of student disciples to carry his teachings forward.

In the summer of 1916, he sought relief with a trip to Mackinac Island in Michigan to escape from the Chicago heat, recurrent attacks of angina pectoris, and increasing debility. Three days after his arrival, he died at the age of 59, succumbing to coronary artery disease, undoubtedly a consequence of his frenetic professional activities.

Bibliography:

Davis, Loyal. J.B. Murphy, stormy petrel of surgery. New York, G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1938.

O'Regan, Suzanne Hart. Lord of the knife: J.B. Murphy, millionaire surgeon: his life in pictures. Amherst, Wisc., Palmer, c1986.

The remarkable surgical practice of John Benjamin Murphy, edited by Robert L. Schmitz and Timothy T. Oh. Urbana, University of Illinois Press, c1993.

Updated: March 5, 2020