By: Katie Lattal, Special Collections Librarian

This November, we are participating in Native American Heritage Month by commemorating Carlos Montezuma, MD. Montezuma was the first Native American student to earn a degree from Northwestern University when he graduated in 1889 with an MD from Chicago Medical College, the medical department of Northwestern (now known as Feinberg School of Medicine).

Carlos Montezuma, MD, 1866-1923

Montezuma lived a truly remarkable life, though he suffered immeasurable childhood trauma. He was originally named Wassaja (Was-SAH-jah), meaning signaling or beckoning, and his family were part of the Yavapai people who lived near Fort McDowell, in what the United States government then called the Arizona Territory. The Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation now occupy a small part of this ancestral territory in the mountainous area northeast of Phoenix.

In 1871, when he was five or six years old, Wassaja was captured by Tohono O'odham (Pima) raiders, separated from his family, and sold to Carlo Gentile. It was Gentile who renamed Wassaja "Carlos Montezuma," after himself. Early accounts of Montezuma’s life depict the relationship between him and Gentile as paternal and warm—and it may have become like that over time—but Montezuma later recounted: “[I] had no idea what would become of me. I was sure of a cruel death or be made to work as a slave forever and ever.”1

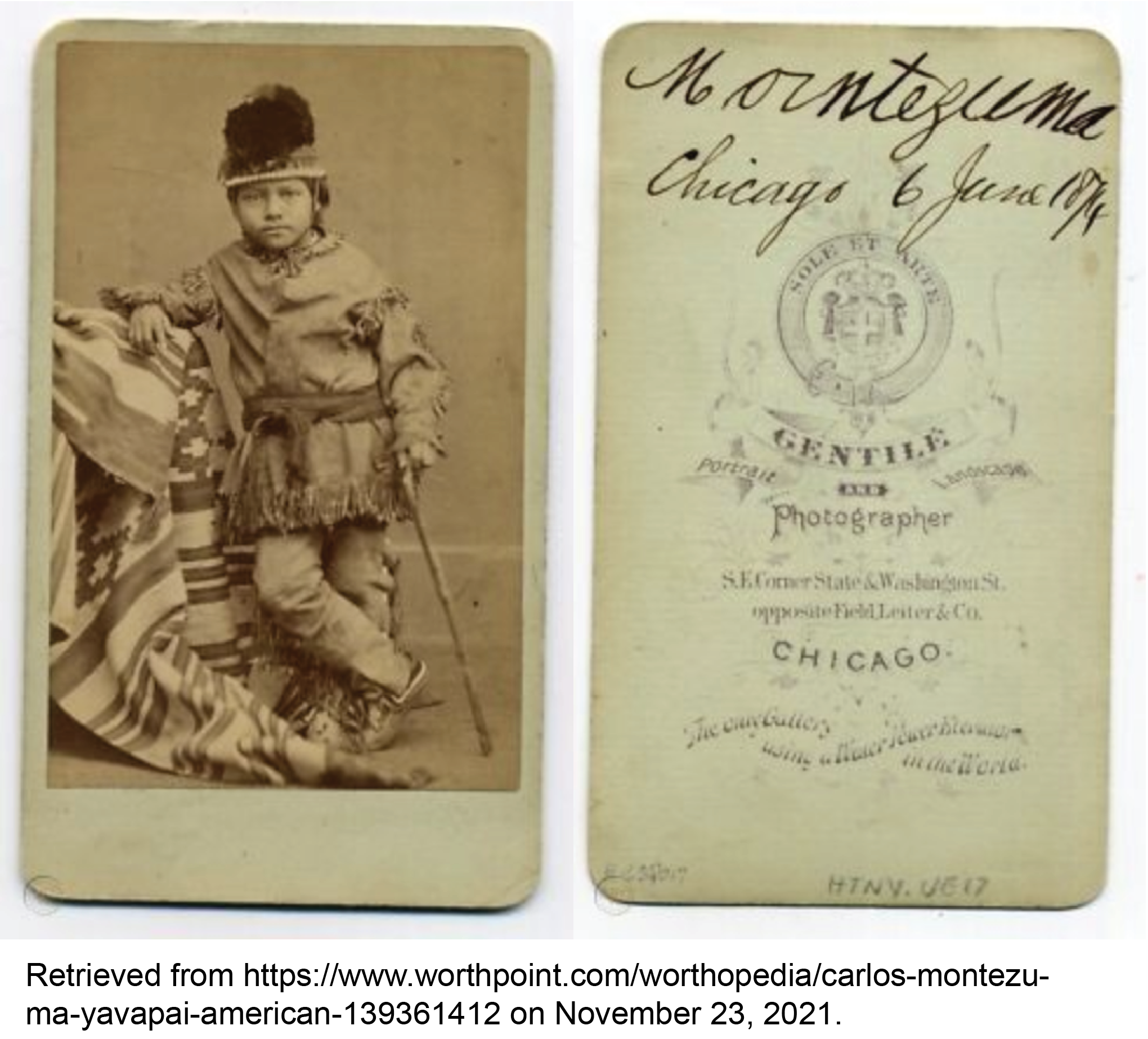

Gentile—an Italian immigrant of some means who dabbled in mining gold and other pursuits in the American West before concentrating on photography—now brought Montezuma on his nonstop travels. In 1872 they stopped in Chicago, where Gentile worked in a gallery. Montezuma attended school, but also performed in one of Buffalo Bill Cody's first stage shows as "Azteka," a stereotypical Indian character (Gentile capitalized on the show; he was the ticket-taker, advertising agent, and sold souvenir photographs to show-goers). They toured with the show until March 1873, and returned to Chicago (and school) for a time. Then after several more years of travel, Gentile sent Montezuma to live with Rev. William H. Stedman in Urbana, IL, where he could have a more stable life. Image at left: Carte-de-visite of Carlos Montezuma taken in 1874 by Carlo Gentile.

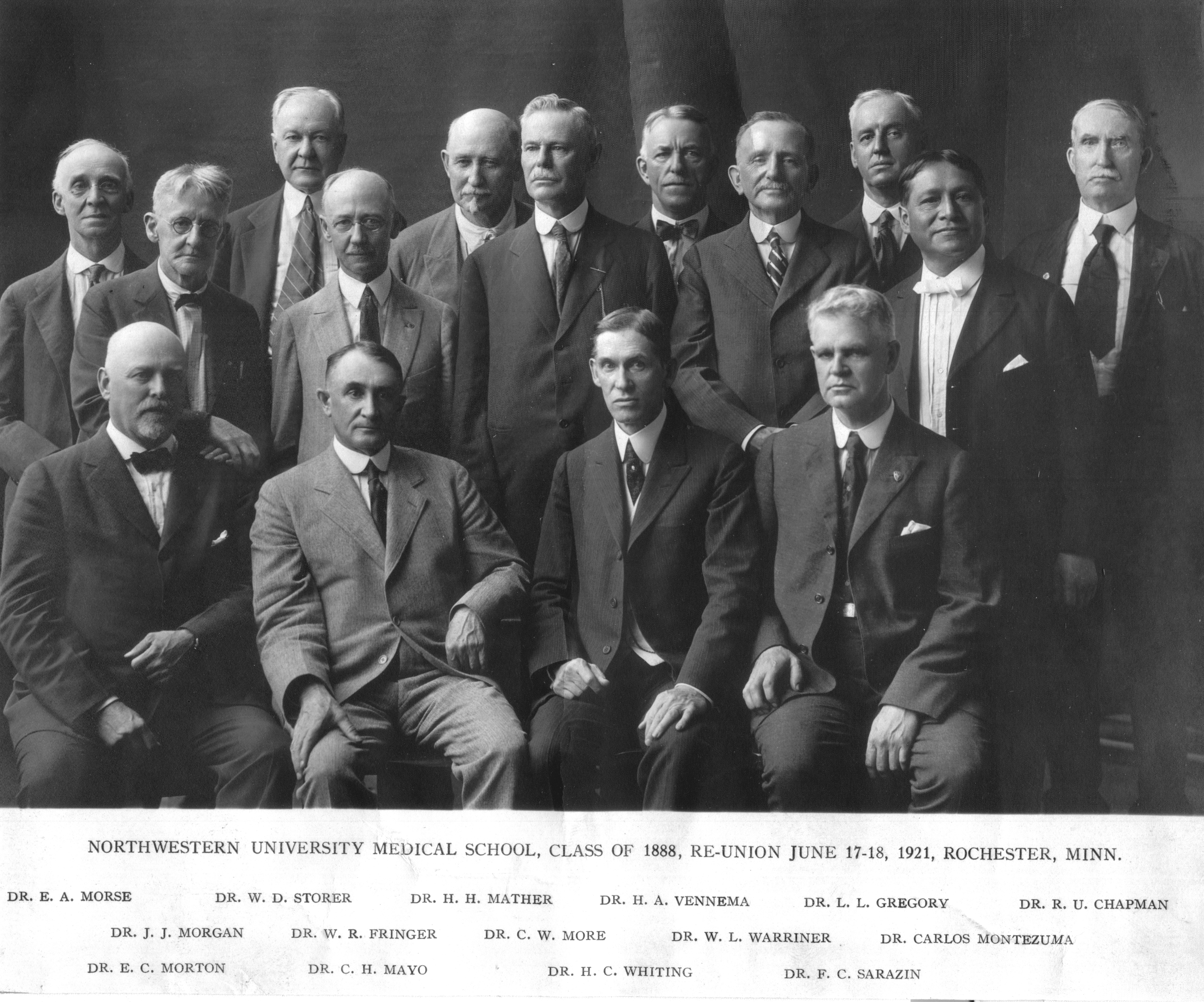

Montezuma was just 14 years old when he matriculated at the University of Illinois in 1880. He wrote articles for the student newspaper and was the president of his class, as well as the president of the Adelphic Debate Society. In 1884 he graduated with a BS in Chemistry, the first Native American student to earn a degree from the University of Illinois. Immediately, Montezuma moved back to Chicago to pursue medicine. He was introduced to John H. Hollister, MD, a founder of Chicago Medical College and the professor of clinical medicine at that time, who promised to remit his tuition. In order to support himself through school, Montezuma worked at a pharmacy and received some financial help from friends. He was originally part of the Class of 1888, but it took him 5 years to finish school because he had to work so much. He officially graduated in 1889, though he built lifelong friendships with those in his original class, such as Charles Mayo. Montezuma became the second American Indian to earn an MD in the United States, the first being Susan La Flesche Picotte, MD (Omaha). Image at right: Carlos Montezuma's Chicago Medical College Class of 1888 portrait, Galter Library Special Collections.

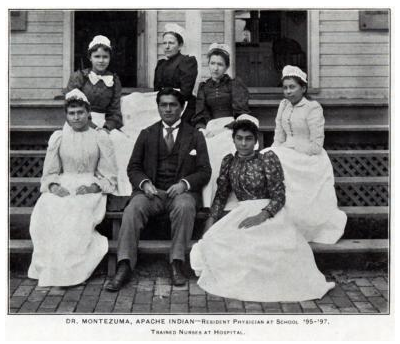

Montezuma first worked as a physician for the Indian Bureau. Within four years he had served at three different Indian Schools and reservations; he decried the squalid conditions of the schools and lack of medical supplies, and experienced a bit of culture shock since he had spent the last 20 years brought up by white people mostly in white urban settings. He finally ended up as the physician at the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania where he stayed for several years. Working at Carlisle brought him closer to Richard Pratt (who had founded the institution in 1879), with whom he had been corresponding since medical school. Montezuma already believed that Indian assimilation into white American culture was the best path to progress for American Indians, and closer proximity to Pratt further fed this belief. Montezuma stayed at Carlisle for three years, and he even served as physician to the famous Carlisle football team.2 Image at left: Carlos Montezuma and six nurses sitting on the steps of the Carlisle Indian School hospital building, Dickinson College Archives & Special Collections; retrieved via Wikipedia on November 23, 2021.

Montezuma returned to Chicago late in 1895, where he reconnected with a medical school classmate, Fenton Turck. Turck brought Montezuma in to his private practice and he became a specialist in gastrointestinal disease. Montezuma made Chicago his home for the rest of his life, and more and more he began to reconnect with his Yavapai roots and his identity as Wassaja. This set in motion a major shift in his beliefs, namely, that the Indian Bureau and reservation system needed to be abolished due to the paternalism of the former and the segregation enacted by the latter.

Instead of total assimilation, Montezuma turned his activism toward Native American civil rights. He had years of experience writing and speaking about his life and beliefs—lectures on American Indian life was one of his paid gigs in medical school, and remember that he was the president of a debate club in college—and he now employed these skills to advocate for the land and water rights of the Yavapais and other Arizona tribes. Montezuma was a founding member of the Society of American Indians (SAI), a diverse group of leading Native progressives and non-native allies who formed the coalition to fight for American Indian interests. The society often clashed on policy and methodology since their specific goals so often differed, but as scholar Tsianina Lomawaima wrote, they firmly supported an “individual Indian’s right to full, valued contribution to the nation's social, economic, and political life.”3 From 1915 to 1922, Montezuma published his own newsletter called, Wassaja: Freedom's Signal for the Indians, which served as his mouthpiece for his views on social justice for Native Americans and his criticism of the Indian Bureau and the SAI.

Montezuma married Marie Keller in 1913, and continued practicing medicine and advocacy work throughout the rest of his life. He opposed the government sending Native soldiers to fight in World War I when they were denied US citizenship, and continued to fight the Indian Bureau over Yavapai land and water rights. He was ultimately successful in ensuring the Yavapai had their own reservation on a portion of their ancestral lands and were not forced onto the nearby Salt River Pima-Maricopa Reservation. In late 1922, Montezuma contracted tuberculosis and realized he was dying. He decided to spend his remaining months in Fort McDowell with his extended family. He died on January 31, 1923. Image at right: Carlos Montezuma (middle row, far right, in tuxedo) with members of the Class of 1888 at a reunion in 1921 in Rochester, MN, Galter Library Special Collections.

Endnotes

1. Quoted in Speroff. Originally from Reel 2, October 7, 1905 in Larner, John William, Jr., Editor, The Papers of Carlos Montezuma, Microfilm Edition, Nine Reels, Scholarly Resources Inc., Wilmington, Delaware, 1984.

2. Carlisle famously beat an undefeated Northwestern in 1903 and their quarterback, Jimmy Johnson, was named to the All-American team that year. Following graduation from Carlisle, Johnson enrolled at Northwestern University Dental School and also played for the Northwestern squad. He earned his DDS in 1907 and returned to Carlisle as assistant coach, where he helped train Jim Thorpe, one of the greatest athletes of the 20th century. He practiced dentistry thereafter.

3. K. Tsianina Lomawaima, “The Mutuality of Citizenship and Sovereignty: The Society of American Indians and the Battle to Inherit America,” in “The Society of American Indians and Its Legacies: A Special Combined Issue of SAIL and AIQ,” special joint issue, Studies in American Indian Literatures 25.2 and American Indian Quarterly 37.3 (Summer 2013): 335. Quoted in Crandall (see below).

Learn More

See the poster display on Montezuma and three other historic graduates on the second floor of Galter Library.

Read biographies of Montezuma:

- Crandall, Maurice. "Carlos Montezuma and the Emergence of American Indian Activism." Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History. 28. Oxford University Press. Published online 28 March 2018: https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.499.

- Iverson, Peter. Carlos Montezuma and the Changing World of American Indians. 1st ed. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1982. Online access and print. Available in the Eckenhoff Reading Room, WZ 100 M781I 1982.

- Speroff, Leon. Carlos Montezuma, M.D.: a Yavapai American Hero: the Life and Times of an American Indian, 1866-1923. Portland, Ore: Arnica Pub., 2003. Online access and print. Available in the Eckenhoff Reading Room, WZ 100 M781S 2003.

Discover Montezuma's papers on microfilm: Montezuma, Carlos, and John W. Larner. The Papers of Carlos Montezuma, M.D.: Including the Papers of Maria Keller Montezuma Moore and the Papers of Joseph W. Latimer. Wilmington, Del: Scholarly Resources, 1983.

Watch the documentary made by UIUC: Carlos Montezuma: Changing is Not Vanishing.

Take the Indigenous Tour of Northwestern virtually or via GPS-guided walking tour.

Digital Primary Resources

Carlos Montezuma Papers, the Newberry Library, Chicago. Finding aid and digital collection.

Carlos Montezuma's Wassaja Newsletter Digitized Collection, Arizona State University.

Photo lot 73, Carlos Montezuma lantern slide collection relating to Arizona Indians circa 1871-1913, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

Carlos Montezuma seated on Carlisle school hospital steps, part of photo lot 81-12, John N. Choate photographs of Carlisle Indian School, circa 1879-1902, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

Updated: November 26, 2023