By: Gabrielle Barr, Research Associate

Mangled faces. Maimed limbs. Rows of feverish men lying in makeshift hospitals. These are the gory images of medical care during the Civil War, some of which were included in the National Library of Medicine’s traveling exhibit, Binding Wounds, Pushing Boundaries: African Americans in Civil War Medicine recently on view at Galter Health Sciences Library & Learning Center. However, as both the NLM exhibit and accompanying staff displays conveyed, medical care was more complex and far-reaching than popular perception suggests. Even something as mundane as record-keeping was a part of the medical experience, and modifications to reporting structure, types of information required, and language used, helped advance knowledge about disease and injury.

The origins of nineteenth-century medical record-keeping

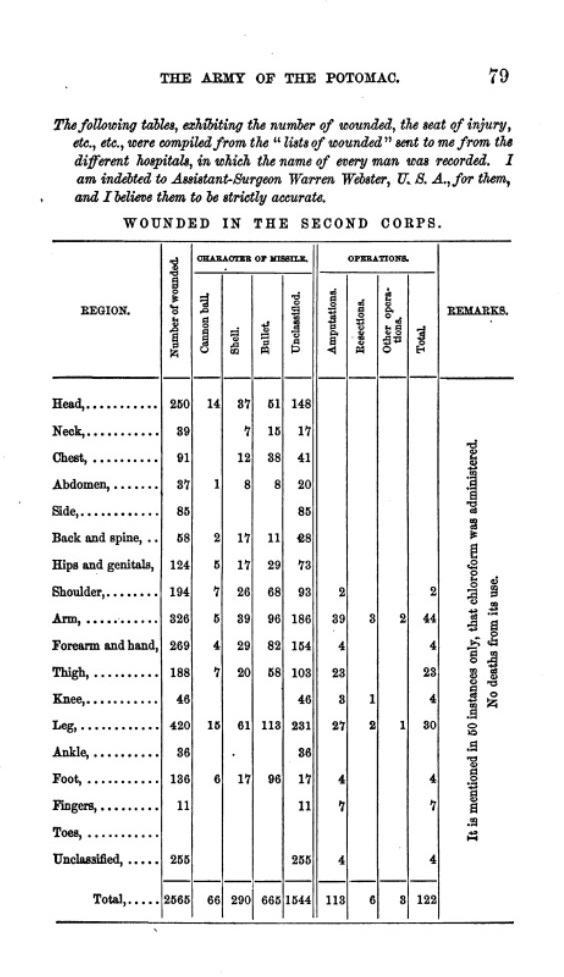

Medical record-keeping in the nineteenth century grew out of a burgeoning enthusiasm for quantification that impacted all aspects of culture. Statistics became increasingly important for managing medical institutions, supporting the polemics of competing medical factions, measuring the need for public health endeavors, and providing authenticity to scientific research. Though the US Army Medical Department had maintained medical records since the 1820s, it was ill-prepared to handle a conflict of such magnitude. Jonathan Letterman, medical director of the Army of the Potomac, instituted several successive reforms beginning in September of 1862. He insisted that captains in newly established ambulance corps make a full disclosure after every action. Letterman decreed that the assistant-surgeon of every regiment submit a complete account of each case brought to the hospital, providing the name, rank, company, regiment, location, character of the injury, treatment, and the outcome. The assistant-surgeon would also be responsible for creating two tabular statements of the wounded exemplified by the chart entitled “Wounded in the Second Corps.”

Medical record-keeping in the nineteenth century grew out of a burgeoning enthusiasm for quantification that impacted all aspects of culture. Statistics became increasingly important for managing medical institutions, supporting the polemics of competing medical factions, measuring the need for public health endeavors, and providing authenticity to scientific research. Though the US Army Medical Department had maintained medical records since the 1820s, it was ill-prepared to handle a conflict of such magnitude. Jonathan Letterman, medical director of the Army of the Potomac, instituted several successive reforms beginning in September of 1862. He insisted that captains in newly established ambulance corps make a full disclosure after every action. Letterman decreed that the assistant-surgeon of every regiment submit a complete account of each case brought to the hospital, providing the name, rank, company, regiment, location, character of the injury, treatment, and the outcome. The assistant-surgeon would also be responsible for creating two tabular statements of the wounded exemplified by the chart entitled “Wounded in the Second Corps.”

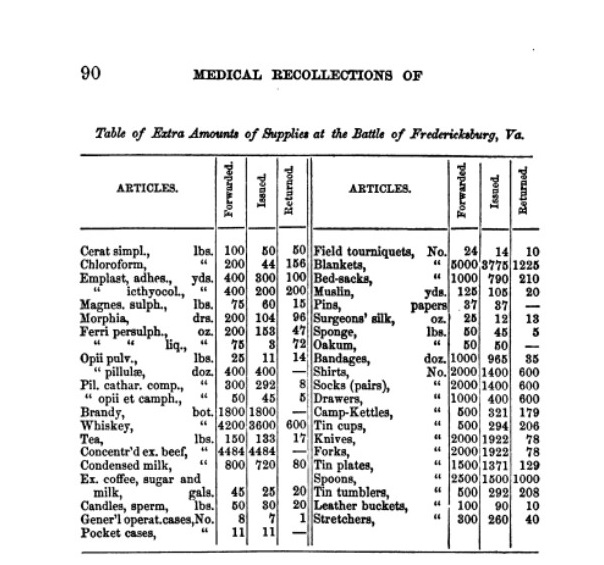

In January of 1863, Letterman issued a decree to the army medical directors to appoint medical inspectors to make monthly reports that included both a standard form as well as an accompanying written report. The monthly reports were designed for medical officers to communicate with the Office of the Surgeon General about issues they were facing as well as to note where deficiencies needed to be addressed. Regimental surgeons were to submit weekly lists of men relieved of duty due to illness, which facilitated assessing the number of men able to fight. Later in the War, Letterman requested reports on matters such as levels of supplies in hospitals, affording the knowledge to prepare facilities for treating troops. Though Letterman pitched the importance of medical record-keeping to army doctors as a scientific enterprise, he also believed the information could avert much of the organizational catastrophes and physical carnage the North experienced at outset of the War.

Widening the scope of inquiry

Like his subordinate Jonathan Letterman, Surgeon General William A. Hammond ascribed to the mid-nineteenth century sanitary philosophy that “the careful recording of vital medical events was as crucial to the management of medical affairs and institutions as bookkeeping was to the nation’s commercial establishments.” In May 1862, he ordered the army’s medical officers to gather and send to Washington unusual anatomical specimens as well as projectiles and foreign objects removed during operations. Physicians were required to write and submit a case history to accompany the specimens. These items would eventually form the collection of the Army Medical Museum, which exists today as the National Museum of Health and Medicine. The following month Hammond widened his scope to include statistics, descriptions, photographs, and drawings that formed the basis of the six volumes of Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. He decided that strengthening existing medical record-keeping mechanisms and supplementing them with special surveys and studies would make the project more successful, and so appointed surgeons, Joseph J. Woodward and John H. Brinton to organize the vast amount of incoming medical and surgical information. Woodward, Brinton, and members of a special medical board reviewed reporting procedures in light of the army’s immediate needs and the requirements of compiling a resource for future use. One of the changes they made was instituting a new statistical classification system based on the model devised by the British epidemiologist, William Farr. These statistics would allow for ready comparison between the North’s Civil War medical experience and the war experiences of other Western countries. Another critical modification to the reporting protocol was the decision to use English instead of Latin words to describe diseases, which ensured the comprehension of recently recruited physicians.

Like his subordinate Jonathan Letterman, Surgeon General William A. Hammond ascribed to the mid-nineteenth century sanitary philosophy that “the careful recording of vital medical events was as crucial to the management of medical affairs and institutions as bookkeeping was to the nation’s commercial establishments.” In May 1862, he ordered the army’s medical officers to gather and send to Washington unusual anatomical specimens as well as projectiles and foreign objects removed during operations. Physicians were required to write and submit a case history to accompany the specimens. These items would eventually form the collection of the Army Medical Museum, which exists today as the National Museum of Health and Medicine. The following month Hammond widened his scope to include statistics, descriptions, photographs, and drawings that formed the basis of the six volumes of Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. He decided that strengthening existing medical record-keeping mechanisms and supplementing them with special surveys and studies would make the project more successful, and so appointed surgeons, Joseph J. Woodward and John H. Brinton to organize the vast amount of incoming medical and surgical information. Woodward, Brinton, and members of a special medical board reviewed reporting procedures in light of the army’s immediate needs and the requirements of compiling a resource for future use. One of the changes they made was instituting a new statistical classification system based on the model devised by the British epidemiologist, William Farr. These statistics would allow for ready comparison between the North’s Civil War medical experience and the war experiences of other Western countries. Another critical modification to the reporting protocol was the decision to use English instead of Latin words to describe diseases, which ensured the comprehension of recently recruited physicians.

Consolidation of practice and legacy

Civil War surgeons and physicians gradually became accustomed to military paperwork and procedures. The consolidation of regimental hospitals into brigade and division facilities as well as the construction of numerous large general hospitals played a role in the efficacy of record-keeping protocols. Over the course of the War, there was a concentrated effort to streamline the routing of medical reports from one command level to another to prevent duplication as well as to eliminate the need for large clerical staffs.

The Civil War placed doctors at the forefront of academic medicine. Military surgeons knew they were taking part in a great historical event and considered maintaining detailed records and performing research their responsibility. The emphasis on record-keeping during the Civil War helped to make the collection of information more uniform, to orient observations and research towards scientific principles, and to create a network of knowledge that linked American physicians with each other as well as their contemporaries overseas. Analysis of the data kept Union physicians abreast of developments regarding diseases and the results of various types of surgery. Hammond’s and Letterman’s emphasis on the scholarly value of medical accounts led to an evolution in Union doctors’ record-keeping. Historian Shauna Devine illustrated this transformation through discussing postmortem reports that increasingly became more analytical and focused on the physiology of disease. Educating subsequent generations about medical techniques and practices was another intended outcome of the widespread record-keeping; however, much of the information amassed became outdated with developments in bacteriology that occurred in the latter part of the nineteenth-century.

Sources consulted

Adams, George Worthington. Doctors in Blue: The Medical History of the Union Army in the Civil War. New York, Henry Schuman, Inc., 1952.

Bollet, Alfred J. Civil War Medicine: Challenges and Triumphs. Tucson, Arizona: Galen Press, LTD, 2002.

Brooks, Stewart. Civil War Medicine. Springfield, Illinois: Charles C. Thomas, 1966.

Cassedy, James H. “Numbering the North’s Medical Events: Humanitarianism and Science in Civil War Statistics.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 66:2 (Summer 1992), 210-233.https://www.jstor.org/stable/44451436

Cunningham, H.H. Doctors in Gray: The Confederate Medical Service. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1958.

Devine, Shauna. Learning from the Wounded: The Civil War and the Rise of American Medical Science. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2014.

Faust, Drew Gilpin. “’Numbers on Top of Numbers’: Counting the Civil War Dead.” The Journal of Military History. 70:4 (Oct.2006), 995-1009. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4138192

Freemon, Frank R. Gangrene and Glory: Medical Care during the American Civil War. London: Associated University Presses, 1998.

Humphreys, Margaret. Marrow of Tragedy: The Health Crisis of the American Civil War. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2013.

Letterman, Jonathan. Medical Recollections of the Army of the Potomac. New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1866.

Miller, Brian Craig. Empty Sleeves: Amputation in the Civil War South. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 2015.

Rutkow, Ira M. Bleeding Blue and Gray: Civil War Surgery and the Evolution of American Medicine. New York: Random House, 2005.

Shryock, Richard H.”A Medical Perspective on the Civil War.” American Quarterly. 14: 2 (Summer 1962), 161-173. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2710639

Willcox, Walter F. “The Development of Military Sanitary Statistics.” Publications of the American Statistical Association. 16:121 (Mar.1918), 907-920. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2964805

Updated: March 5, 2020