Introduction

On October 14, 1912, a delusional saloonkeeper shot Theodore Roosevelt as he campaigned for an unprecedented third term as president. After delivering a 50-page speech with blood dripping from his wounded chest, Roosevelt was brought from Milwaukee to Chicago, where he was met by the renowned and controversial surgeon – and Northwestern professor – John Benjamin Murphy.

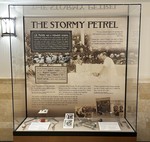

The Stormy Petrel & the Bull Moose: J.B. Murphy and the Attempted Assassination of Theodore Roosevelt, on display in the Eisenberg Gallery (the hallway connecting the Ward Building and the Method Atrium), tells the story of the chance encounter between these larger-than-life figures in American history, exploring Murphy’s colorful career as well as the aftermath of Roosevelt’s shooting.

Artifacts on display include Murphy’s personal surgical instruments. Most of these items were donated in 2021 by Chicago’s Mercy Hospital, where Murphy was surgeon-in-chief and where he gave his world-famous surgical demonstrations. This important gift supplements Galter’s existing Murphy collections, including personal papers and items donated by Murphy’s great-granddaughter, Barbara Miller, in 2010. Also on display is a Murphy button, the most famous of Murphy’s surgical innovations; this rare item was part of a 2013 gift from Julie Smith, MD.

Credits

J.B. Murphy was a renowned surgeon, internationally recognized for his superb technical skill, clinical expertise, and innovation across surgical specialties. By 1912, he had written over 100 articles, served as President of the American Medical Association, and held the positions of Chief of Surgery at Mercy Hospital and Chair of the Department of Surgery at Northwestern University Medical School, predecessor of Feinberg School of Medicine.

He was a dramatic figure in the operating room. With instrument in hand, he fairly thrilled the audience.

William J. Mayo. “In Memoriam.” The Clinics of John B. Murphy, M.D., at Mercy Hospital.

Despite his greatness in many particulars, Dr. Murphy had a singular ability to arouse envy, distrust, and dislike.

Leslie Arey, Northwestern University Medical School 1859- 1979: A Pioneer in Educational Reform.

Loyal Davis dubbed Murphy “the stormy petrel of surgery” because he was often a harbinger of conflict, just as sailors thought stormy petrels presaged approaching storms. Murphy had a “personal genius for creating virulent opposition.” (Book Notice: J. B. Murphy, Stormy Petrel of Surgery, JAMA.)

[Patients’] attitude, at which I always marveled, was that if Murphy couldn’t do it, it couldn’t be done; it was the will of God.

Paul Magnuson, Ring the Night Bell. Founder of Shirley Ryan AbilityLab (formerly RIC).

You could be sure that life with John Benjamin Murphy would never be dull. His restless energy, flamboyant personality and superb technic, his daring in trying the new and unorthodox, his personal feuds with half the other surgeons in town, combined to create an atmosphere of excitement, of being on the inside of the greatest and most dramatic developments in the whole world of medicine at that time.

Paul Magnuson, Ring the Night Bell.

On October 14, 1912, Teddy Roosevelt was shot on his way to give a campaign speech in Milwaukee. John Schrank, the assassin, sought to keep Roosevelt from a third term as President. After ensuring Schrank was safe from the crowd, Roosevelt proceeded to the venue to deliver his speech, famously speaking for over an hour while bleeding from the chest. His folded 50 page speech and his spectacle case slowed the bullet.

Friends, I shall have to ask you to be as quiet as possible. I do not know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot, but it takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose. But, fortunately, I had my manuscript, so, you see, I was going to make a long speech. And, friends, there is a bullet—there is where the bullet went through, and it probably saved the bullet from going into my heart.

Roosevelt prefacing his speech at the Auditorium in Milwaukee not long after he was shot.

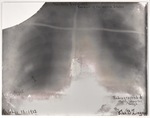

Roosevelt traveled to Chicago for treatment, where four leading surgeons were to coordinate his care. J.B. Murphy met Roosevelt’s train ahead of his colleagues—either coincidentally or deliberately—and thereafter managed Roosevelt’s care at Mercy Hospital. The doctors’ decision not to remove the bullet was based on x-ray images, a relatively new diagnostic tool. X-rays confirmed that the bullet had not penetrated the lung, but was too deeply imbedded in the chest cavity to remove safely.

There was only room enough for one actor when J.B. held forth. Like Theodore Roosevelt, if it was a wedding, he wanted to be the bride, if it was a funeral, he envied the corpse.

Archibald Church, in a letter to Loyal Davis on the publication of Davis’ book, J.B. Murphy, Stormy Petrel of Surgery. It is a variation of a witticism about Roosevelt coined by his daughter Alice Roosevelt Longfellow and echoed by many.

Murphy developed diagnostic techniques that bore his name, such as Murphy’s punch for kidney infections, Murphy’s sequence for appendicitis, and Murphy’s sign and Murphy’s test for cholecystitis. Most famous of his innovations was the Murphy button, a device which revolutionized abdominal surgery.

“An epoch-making invention in surgery of the intestines”

Murphy became world-renowned in 1893 for his button, a device that enabled the surgical connection of tubular structures like intestines and arteries, a process known as anastomosis. Until the Murphy Button, gastrointestinal surgeries were largely unsuccessful due to the elevated risk of fatal infection.

1. Murphy button — to perform vascular, intestinal, or biliary anastomosis

2. Rubber-covered vessel clamps — for controlling hemorrhage during vascular anastomosis

3. Curved hemostatic forceps — to control bleeding

4. Needles and sutures — to sew a stitch along the incision that, when pulled, tightens around the button, holding the tissues together to heal

“A well functioning joint”

Arthroplasty aims to restore the function of a joint and alleviate pain. Rather than the total joint replacements practiced today, Murphy’s practice was to reshape the bone, using some of the instruments below. Murphy boasted that he achieved a perfect result on his first hip joint arthroplasty.

1. End mill with handle — to smooth the hip socket

2. Reamer & end mill (later era) — to resurface the hip socket and femoral head

3. Tendon tunneling forceps — for grasping and directing severed tendons and tendon grafts

4. Periosteal elevator — to lift soft tissues during surgery

5. Handmade mallet & chisel — for separation or removal of fused bone

6. Bone gouge — for scraping and shaping bone

7. Retractors (2) — to hold incisions open

- Arey, Leslie. Northwestern University Medical School 1859- 1979: A Pioneer in Educational Reform. Chicago: Northwestern University, 1979. https://doi.org/10.18131/g3-7a5p-zy02

- “Book Notices: J. B. Murphy, Stormy Petrel of Surgery.” Journal of the American Medical Association 111, no. 1 (July 2, 1938): 91-92, https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/issue/111/1

- Clough, Joy. In Service to Chicago: The History of Mercy Hospital. Chicago: Mercy Hospital, 1979.

- Davis, Loyal. J. B. Murphy, Stormy Petrel of Surgery. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1938.

- Gould, Lewis L., ed. Bull Moose on the Stump: The 1912 Campaign Speeches of Theodore Roosevelt. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2008.

- Helferich, Gerard. Theodore Roosevelt and the Assassin: Madness, Vengeance, and the Campaign of 1912. Guilford, CT: Lyons Press, 2013.

- History of Medicine and Surgery and Physicians and Surgeons of Chicago. Chicago: The Biographical Publishing Corporation, 1922.

- Magnuson, Paul B. Ring the Night Bell: The Autobiography of a Surgeon. Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1960. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.547360

- Remey, Oliver E., Henry F. Cochems, and Wheeler P. Bloodgood. The Attempted Assassination of Ex-President Theodore Roosevelt. Milwaukee: The Progressive Publishing Company, 1912.

- Schmitz, Robert L., and Timothy T. Oh. The Remarkable Surgical Practice of John Benjamin Murphy. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993.

- Skillern, P. G., Jr., ed. “In Memoriam.” The Clinics of John B. Murphy, M.D., at Mercy Hospital, Chicago 5, no. 6, (1916): 989-1000. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015077335498&seq=21

Exhibit Details

In October 1912, a would-be assassin's bullet brought former president Theodore Roosevelt into the path of renowned Chicago surgeon John Benjamin Murphy. This exhibit tells the story of the chance encounter between these larger-than-life figures in American history, exploring Murphy’s colorful career as well as the aftermath of Roosevelt’s shooting.

-

- Location

- Eisenberg Gallery

- Date

- Jul 18, 2023 - Present

- Contact

- ghsl-specialcollections@northwestern.edu

- Subjects

- northwestern

- american history

- 20th century

- surgery

- political history

- chicago