Introduction

The 18th century was an age of experimentation in Europe. The scientific revolution of earlier centuries and the emphasis on reason and learning fostered by the Enlightenment allowed scientists to explore the workings of nature like never before. In this world of scientific inquiry, the study of electricity captured the imaginations of scholars and the public alike. Once scientists discovered how to create and store electrical charges, they harnessed the current in a wide range of experiments, from the practical and informative to the entertaining and bizarre. Of particular interest were its potential medical uses—How did it affect the body? Could it treat disease? Would it reanimate the dead?

This exhibit, and its companion Reconstructing the Body, were created in conjunction with the National Library of Medicine traveling exhibit, Frankenstein: Penetrating the Secrets of Nature, which explores the power of Mary Shelley's novel to expose hidden fears of science and technology as human efforts to penetrate the secrets of nature continue.

Reviviendo el cuerpo: La ciencia, Frankenstein, y la "chispa vital"

El siglo XVIII fue una época de experimentación en Europa. La revolución científica de siglos anteriores y el énfasis en la razón y el aprendizaje promovidos por la Ilustración permitieron a los científicos explorar el funcionamiento de la naturaleza como nunca antes. En este ambiente de investigación científica, el estudio de la electricidad capturó la imaginación de académicos y del público en general. Una vez que los científicos descubrieron cómo crear y almacenar cargas eléctricas, utilizaron la corriente en una amplia gama de experimentos, desde prácticos e informativos hasta entretenidos y extraños. Les interesaba en particular explorar sus posibles usos médicos: ¿cómo afectaba al cuerpo? ¿Podría tratar enfermedades? ¿Reviviría a los muertos?

Esta exposición, y su compañera Reconstruyendo el cuerpo, se crearon en conjunto con la exhibición itinerante de la Biblioteca Nacional de Medicina, Frankenstein: Penetrando los secretos de la naturaleza, que explora el poder de la novela de Mary Shelley para exponer los miedos ocultos de la ciencia y la tecnología a medida que continúan los esfuerzos humanos por penetrar los secretos de la naturaleza.

Credits

Curated and designed by Emma Florio, MLIS; Katie Lattal, MA; Lindsey O'Brien, MSLIS; and Annie Wescott, MLIS.

Curada y diseñada por Emma Florio, MLIS; Katie Lattal, MA; Lindsey O'Brien, MSLIS; y Annie Wescott, MLIS.

Spanish language translation provided by Multilingual Connections.

Electrifying Experiments

To understand electricity, scientists experimented with it in any way they could.

Above: Here Jean Antoine Nollet reproduces Stephan Gray's “electric boy” experiment. An electrically charged boy hangs from insulating silk ropes and the scientist demonstrates how objects are statically drawn to his hands. A woman bends forward to poke the boy’s nose to get an electric shock. This memorable demonstration illustrates that the human body can conduct electricity. Frontispiece illustration. Nollet. Essai sur l'electricité des corps. Paris: Chez les freres Guerin, 1746.

Below: By the early 19th century, laypeople could acquire electrical apparatuses and perform experiments themselves, as in this painting where a family uses an electrifying machine to pass a current through their joined hands. Diana Sperling. May 25th. Henry Van electrifying -- Mrs. Van, Diana, Harry, Isabella, Mum, and HGS. Dynes Hall, ca. 1812-1823. Watercolor.

Galvanism

One notable scientist who experimented with electricity was Italian physician Luigi Galvani (1737–1798). Using dissected animal legs, he observed that muscles contracted and spasmed when stimulated by an electric current. Galvani believed this was due to an internal electricity inherent in animal tissue, which he called “animal electricity,” or galvanism. In his mind, this physical and metaphorical “spark” was a vital force that animated all living creatures. Although his theories were disproven, the “spark of life” theory proved intriguing to both scientists and artists, like Mary Shelley.

Right: portrait of Galvani.

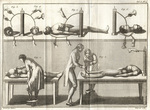

Above: This print depicts Galvani’s famous experiments applying electric current to frogs’ legs in different variations, making them twitch. Also depicted are a lamb (Fig. 19) and a chicken leg (Fig. 20). Tabula VI. Galvani, Luigi. Opere edite ed inedite del professore Luigi Galvano. Bologna: E. dall’Olmo, 1841.

Masters of the Macabre

Scientists held public demonstrations of electricity as both experiments and entertainment. Galvani’s nephew, Giovanni Aldini (1762-1834), took his uncle’s animal experiments further: he performed public demonstrations using bodies of executed criminals, the only bodies legally available to science at the time. In 1803, he electrified the body of George Foster at Newgate Prison in London. For seven hours, in front of an amazed audience, he made the body move in ways he described as giving an “appearance of reanimation.”

In 1818, anatomist James Jeffray, assisted by physician Andrew Ure, performed an experiment similar to Aldini’s with the body of Matthew Clydesdale at the University of Glasgow, seen at right. Aldini believed galvanism could be used for resuscitation, but Jeffray and Ure believed electrifying a corpse could potentially bring it back to life.

Ure vividly described the results of his and Jeffray’s experiment in a journal article:

[When stimulating the supraorbital nerve in the forehead]... every muscle in his countenance was simultaneously thrown into fearful action; rage, horror, despair, anguish, and ghastly smiles, united their hideous expression in the murderer's face... At this period several of the spectators were forced to leave the apartment from terror or sickness, and one gentleman fainted.

Above: “Le docteur Ure galvanisant le corps de l’assassin Clydsdale.” In Louis Figuier. Les merveilles de la science. Paris: Furne, Jouvet et Cie, 1867.

Reviving the Apparently Dead

As experiments with electricity continued, interest in the physiology of death and possibilities of resuscitation grew. By the late 18th century, physicians had learned to distinguish between apparent death– when the patient only appeared dead and could be successfully resuscitated–and absolute death, which was irreversible.

Naturally, there was speculation that electricity could be used for resuscitation from apparent death. In 1809, Scottish surgeon Allan Burns first suggested a combination of electric shock and mouth-to-mouth ventilation, now commonly employed as cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). Giovanni Aldini also advocated for electricity as the primary means of resuscitation.

It was in this scientific atmosphere an eighteen-year-old Mary Shelley (then Godwin) and her future husband Percy Shelley visited Lord Byron’s Alpine Villa in 1816. As entertainment, they competed to write ghost stories; Mary Shelley settled on the idea of a man-made creature, reanimated from death.

Galvanism and Frankenstein

Galvani’s idea of a “spark of life” influenced Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Shelley recalls her 1816 stay at Lord Byron’s villa in the preface to the 1831 edition of Frankenstein:

Many and long were the conversations between Lord Byron and Shelley, to which I was a devout but nearly silent listener. During one of these, various philosophical doctrines were discussed, and among others the nature of the principle of life, and whether there was any probability of its ever being discovered and communicated. …Perhaps a corpse would be re-animated; galvanism had given token of such things: perhaps the component parts of a creature might be manufactured, brought together, and endued with vital warmth.

Above: This print depicts Aldini’s experiments applying electric current to corpses. Plate 4, vol. 1. Aldini, Giovanni. Essai théorique et expérimental sur le galvanisme. Paris: Fournier fils, 1804.

Shelley invents Victor Frankenstein, a student of chemistry, whose studies lead him to discover how to reconstruct and reanimate a human being. His experiments with human remains and his own words echo the desires of James Jeffray and Andrew Ure:

….if I could bestow animation upon lifeless matter, I might in process of time (although I now found it impossible) renew life where death had apparently devoted the body to corruption.

Victor borrows the language of galvanism to describe bringing his creation to life:

I collected the instruments of life around me, that I might infuse a spark of being into the lifeless thing that lay at my feet. It was already one in the morning; the rain pattered dismally against the panes, and my candle was nearly burnt out, when, by the glimmer of the half-extinguished light, I saw the dull yellow eye of the creature open; it breathed hard, and a convulsive motion agitated its limbs.

Frankenstein, Volume 1, Chapter 4

Shelley's word choice evokes galvanism here. In addition to the “spark of being,” the convulsions and agitations of the Creature recall the galvanic experiments that used electricity to cause muscle contractions in dead animals and humans, making them appear alive. Victor’s work by “half-extinguished” candlelight not only points to the secretive nature of his work, but further draws parallels between fire and electricity, as well as the boundary between life and death.

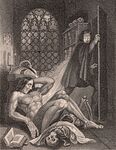

At right: Frontispiece. Shelley, Mary. Frankenstein. London: Colburn and Bentley, 1831.

From Science Fiction to Science Fact: The AED

While Victor Frankenstein was a fictional scientist, experiments such as Galvani’s did inspire real progress in the medical field, such as in the development of resuscitation technology. Further experimentation in the 19th and 20th centuries led to the development of the automatic external defibrillator (AED), a device that uses an electric current to reestablish a normal heart rhythm in patients experiencing life-threatening fibrillation (irregular contraction of the cardiac muscles) and tachycardia (abnormally fast heart rate). Within 30 years, AED devices became a vital part of emergency medicine.

Timeline of the AED

1899 - Italian physiologists demonstrate that electric currents can both stop and restart the heart

1947 - American cardiac surgeon Claude Beck performs the first successful internal defibrillation on a human, by putting paddles (above) directly on a patient’s heart

1950s - American cardiologist Paul Zoll and engineer William Kouwenhoven develop external defibrillators that use alternating current; they are heavy and the voltage can damage the heart

1962 - American cardiologist Bernard Lown helps develop a defibrillator that uses direct current, which is safer and easier to use

1968 - Northern Irish cardiologist Frank Pantridge (above) develops the first portable defibrillator, weighing 7 pounds

1978 - First “fool proof” portable AED that can be used by laypeople is developed

1980 - First implantable cardioverterdefibrillator (ICD) is surgically placed in a patient

2001 - FDA approves a wearable cardioverterdefibrillator vest (above)

Experimentos electrizantes

Para comprender la electricidad, los científicos experimentaron con ella de todas las formas posibles.

Arriba: Aquí, Jean Antoine Nollet reproduce el experimento del “niño eléctrico” de Stephan Gray. Un niño cargado eléctricamente cuelga de unas cuerdas de seda aislantes y el científico demuestra cómo los objetos son atraídos estáticamente hacia sus manos. Una mujer se inclina hacia delante para tocar la nariz del niño y recibir una descarga eléctrica. Esta memorable demostración ilustra que el cuerpo humano puede ser conductor de electricidad. Ilustración del frontispicio. Nollet. Ensayo sobre la electricidad de los cuerpos. París: En casa de los hermanos Guerin, 1746.

Abajo: A principios del siglo XIX, las personas no especializadas podían adquirir aparatos eléctricos y realizar experimentos por sí mismos, como en esta pintura donde una familia utiliza una máquina electrificadora para pasar una corriente a través de sus manos unidas. Diana Sperling. 25 de mayo. Electrificación de Henry Van -- Sra. Van, Diana, Harry, Isabella, mamá, y HGS. Dynes Hall, alrededor de 1812-1823. Acuarela.

Galvanismo

Un científico notable que experimentó con la electricidad fue el médico italiano Luigi Galvani (1737-1798). Utilizando patas de animales disecadas, observó que los músculos se contraían y sufrían espasmos cuando eran estimulados por una corriente eléctrica. Galvani creía que esto se debía a una electricidad interna inherente al tejido animal, a la que llamó “electricidad animal” o galvanismo. En su mente, esta “chispa” física y metafórica era una fuerza vital que animaba a todas las criaturas vivientes. Aunque sus teorías fueron refutadas, la teoría de la “chispa vital” resultó fascinante tanto para los científicos como para los artistas, como Mary Shelley.

A la derecha: retrato de Galvani

Arriba: Esta impresión muestra los famosos experimentos de Galvani en los que aplicaba corriente eléctrica a las ancas de ranas en distintas variaciones, lo que las hacía temblar. También se muestran un cordero (Fig. 19) y una pata de gallina (Fig. 20). Tabla VI. Galvani, Luigi. Obra editada e inédita del profesor Luigi Galvano. Bolonia: E. dall’Olmo, 1841.

Maestros de lo macabro

Los científicos realizaron demostraciones públicas de electricidad para experimentar y entretener. El sobrino de Galvani, Giovanni Aldini (1762-1834), llevó los experimentos con animales de su tío un paso más allá: realizó demostraciones públicas utilizando cuerpos de criminales ejecutados, los únicos cuerpos legalmente disponibles para la ciencia en ese momento. En 1803, electrificó el cuerpo de George Foster en la prisión de Newgate en Londres. Durante siete horas, frente a un público asombrado, hizo que el cuerpo se moviera de maneras que, según él, daban una “apariencia de reanimación.”

En 1818, el anatomista James Jeffray, con la ayuda del médico Andrew Ure, realizó un experimento similar al de Aldini con el cuerpo de Matthew Clydesdale en la Universidad de Glasgow, que se puede apreciar a la derecha. Aldini creía que el galvanismo podía utilizarse para la reanimación, pero Jeffray y Ure pensaban que la electrificación de un cadáver podría devolverle la vida.

Ure describió meticulosamente los resultados de su experimento y el de Jeffray en un artículo de revista:

[Al estimular el nervio supraorbitario en la frente]... cada músculo de su rostro se puso simultáneamente en acción temerosa; rabia, horror, desesperación, angustia y sonrisas espantosas se unieron para conformar una expresión espantosa sobre el rostro del asesino... En ese momento, varios de los espectadores se vieron obligados a abandonar el apartamento por terror o náuseas, e incluso un caballero se desmayó.

A la derecha: “El doctor Ure galvaniza el cuerpo del asesino Clydsdale”. En Louis Figuier. Las maravillas de la ciencia. París: Furne, Jouvet et Cie, 1867.

Reviviendo a los aparentemente muertos

A medida que se realizaban experimentos con electricidad, aumentó el interés por la fisiología de la muerte y las posibilidades de reanimación. A finales del siglo XVIII, los médicos habían aprendido a distinguir entre la muerte aparente (cuando el paciente solo parecía muerto y podía ser reanimado con éxito) y la muerte absoluta, que era irreversible.

Naturalmente se especuló con la posibilidad de utilizar la electricidad para resucitar a un paciente que parecía estar muerto. En 1809, el cirujano escocés Allan Burns fue el primero en sugerir una combinación de descargas eléctricas y respiración boca a boca, que ahora se emplea comúnmente como reanimación cardiopulmonar (RCP). Giovanni Aldini también defendió el uso de la electricidad como principal método de reanimación.

Fue en este ambiente científico cuando Mary Shelley (entonces Godwin), de dieciocho años de edad, y su futuro esposo Percy Shelley visitaron la Villa Alpina de Lord Byron en 1816. Para entretenerse, hicieron una competencia para escribir historias de fantasmas; Mary Shelley se decidió por la idea de una criatura creada por el ser humano, reanimada de la muerte.

Galvanismo y Frankenstein

La idea de Galvani de la “chispa vital” influyó en Frankenstein de Mary Shelley. Shelley recuerda su estancia en la villa de Lord Byron en 1816 en el prefacio de la edición de 1831 de Frankenstein:

Muchas y largas fueron las conversaciones entre Lord Byron y Shelley, de las que yo era una oyente devota pero casi silenciosa. Durante una de ellas, se discutieron varias doctrinas filosóficas; entre otras, la naturaleza del principio de la vida, y si había alguna probabilidad de que alguna vez fuera descubierto y comunicado... Tal vez pudiera reanimarse un cadáver, el galvanismo había dado indicios de tales cosas: tal vez pudieran fabricarse las partes componentes de una criatura, reunirlas y dotarlas de calor vital.

Arriba: Esta impresión muestra los experimentos de Aldini aplicando corriente eléctrica a cadáveres. Impresión 4, vol. 1. Aldini, Giovanni. Ensayo teórico y experimental sobre el galvanismo. París: Fournier fils, 1804.

Shelley inventa a Víctor Frankenstein, un estudiante de química, cuyas investigaciones lo llevan a descubrir cómo reconstruir y reanimar a un ser humano. Sus experimentos con restos humanos y sus declaraciones hacen eco a las aspiraciones de James Jeffray y Andrew Ure:

...si podía dar animación a la materia sin vida, podría, con el tiempo (aunque ahora me parecía imposible), renovar la vida allí donde la muerte había entregado aparentemente el cuerpo a la corrupción.

Víctor utiliza el lenguaje del galvanismo para describir cómo da vida a su creación:

Reuní a mi alrededor los instrumentos, que infundirían una chispa vital a la cosa sin vida que yacía a mis pies. Era la una de la madrugada; la lluvia golpeaba desoladoramente contra los cristales, y mi vela se hallaba casi consumida, cuando, gracias al resplandor de la luz agonizante, vi abrirse el ojo amarillo y apagado de la criatura; respiró con dificultad, y un movimiento convulsivo agitó sus miembros.

Frankenstein, Volumen 1, Capítulo 4

Las palabras de Shelley evocan el galvanismo en este punto. Además de la “chispa vital,” las convulsiones y agitaciones de la Criatura recuerdan aquellos experimentos con el galvanismo donde se utilizaron corrientes eléctricas para causar la contracción de músculos en animales y seres humanos muertos, haciéndolos parecer vivos. El trabajo de Víctor, ejecutado a la luz de una vela “medio apagada,” no solo debe realizarse en secreto, sino que también establece paralelos entre el fuego y la electricidad, y explora los límites entre la vida y la muerte.

A la derecha: Frontispicio. Shelley, Mary. Frankenstein. London: Colburn and Bentley, 1831.

De la ciencia ficción a la ciencia real: el DEA

Aunque Víctor Frankenstein fue un científico ficticio, experimentos como el de Galvani inspiraron verdaderos progresos en el campo de la medicina, como el desarrollo de la tecnología de reanimación. Experimentos posteriores en los siglos XIX y XX condujeron al desarrollo del desfibrilador externo automático (DEA), un dispositivo que utiliza una corriente eléctrica para restablecer un ritmo cardíaco normal en pacientes que experimentan episodios de fibrilación (contracción irregular de los músculos cardíacos) y taquicardia (frecuencia cardíaca anormalmente rápida) potencialmente mortales. En 30 años, los dispositivos DEA se convirtieron en una parte vital de la medicina de emergencia.

Línea de tiempo del DEA

1899 - Fisiólogos italianos demuestran que las corrientes eléctricas pueden tanto detener como reiniciar el corazón

1947 - El cirujano cardíaco estadounidense Claude Beck realiza la primera desfibrilación interna exitosa en un ser humano, colocando paletas (arriba) directamente sobre el corazón del paciente

1950s - El cardiólogo estadounidense Paul Zoll y el ingeniero eléctrico William Kouwenhoven desarrollan desfibriladores externos que utilizan corriente alterna. Son pesados y el voltaje puede lesionar el corazón

1962 - El cardiólogo estadounidense Bernard Lown ayuda a desarrollar un desfibrilador que utiliza corriente continua, que es más seguro y fácil

1968 - El cardiólogo norirlandés (arriba) Frank Pantridge desarrolla el primer desfibrilador portátil, que pesa 7 libras

1978 - Se desarrolla el primer DEA portátil “a prueba de errores” para uso de personas no especializadas

1980 - Se coloca quirúrgicamente el primer desfibrilador automático implantable (DAI) en un paciente

2001 - La FDA aprueba un chaleco desfibrilador cardioversor portátil (arriba)

Primary Resources

- Aldini, Giovanni. Essai théorique Et Expérimental Sur Le Galvanisme: Avec Une Série D'expériences Faites En Présence Des Commissaires De L'institut National De France, Et En Divers AmphithéAares Anatomiques De Londres. Paris: Fournier fils, 1804.

- Aldini, John. An Account of the Late Improvements in Galvanism. London: Cuthell and Martin, J. Murray, 1803. https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/an-account-of-the-late-improvements-in-galvanism-1803/.

- ———. General Views on the Application of Galvanism to Medical Purposes; Principally in Cases of Suspended Animation. London: Sold by J. Callow [and 2 others], 1819.

- Figuier, Louis. "Le Docteur Ure Galvanisant Le Corps De L'assassin Clydsdale [Illustration]." In Les Merveilles De La Science. Paris: Furne, Jouvet et Cie, 1867.

- Galvani, Luigi, Silvestro Gherardi, Giuseppe Venturoli, and Bassiano Carminati. Opere Edite Ed Inedite Del Professore Luigi Galvano Raccolte E Pubblicate Per Cura Dell'accademia Delle Scienze Dell'istituto Di Bologna. Bologna: Tip. di E. dall'Olmo, 1841.

- Nollet, Jean-Antoine. "[The Electric Boy] [Frontispiece]." In Essai Sur L'electricité Des Corps. Paris: Chez les freres Guerin, 1746.

- Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft. Frankenstein: Or, the Modern Prometheus. Rev., corr., & illus. ed. London: Colburn and Bentley, 1831. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/42324/42324-h/42324-h.htm.

- Sperling, Diana. "May 25th. Henry Van Electrifying -- Mrs. Van, Diana, Harry, Isabella, Mum, and Hgs. Dynes Hall [Watercolor]." ca. 1812-1823. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:May_25th._Henry_Van_electrifying_--_Mrs._Van,_Diana,_Harry,_Isabella,_Mum,_and_HGS._Dynes_Hall.jpg.

- Ure, Andrew. "An Account of Some Experiments Made on the Body of a Criminal Immediately after Execution, with Physiological and Practical Observations." Journal of Science and the Arts 6 (1819): 283-94.

Secondary Resources

- Adee, Sally. "Spectacular Pseudoscience: The Fall and Rise of Bioelectricity." In We Are Electric: Inside the 200-Year Hunt for Our Body’s Bioelectric Code and What the Future Holds. New York: Hachette, February 28, 2023.

- AlGhatrif, Majd, and Joseph Lindsay. "A Brief Review: History to Understand Fundamentals of Electrocardiography." [In eng]. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect 2, no. 1 (2012). https://doi.org/10.3402/jchimp.v2i1.14383.

- Alzaga, Ana Graciela, Joseph Varon, and Peter Baskett. "Charles Kite: The Clinical Epidemiology of Sudden Cardiac Death and the Origin of the Early Defibrillator." Resuscitation 64, no. 1 (2005): 7-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.11.011.

- Ball, Christine M., and Peter J. Featherstone. "Early History of Defibrillation." [In eng]. Anaesth Intensive Care 47, no. 2 (Mar 2019): 112-15. https://doi.org/10.1177/0310057x19838914.

- Bennett, Rachel E. "A Fate Worse Than Death? Dissection and the Criminal Corpse." In Capital Punishment and the Criminal Corpse in Scotland, 1740–1834 London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK481735/.

- Bertucci, P. "Sparks in the Dark: The Attraction of Electricity in the Eighteenth Century." [In eng]. Endeavour 31, no. 3 (Sep 2007): 88-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.endeavour.2007.06.002.

- Bresadola, Marco. "Medicine and Science in the Life of Luigi Galvani (1737–1798)." Brain Research Bulletin 46, no. 5 (1998/07/15): 367-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0361-9230(98)00023-9.

- Davidson, Luke A. F. "Raising up Humanity: A Cultural History of Resuscitation and the Royal Humane Society of London, 1774-1808." Doctor of Philosophy, University of York, 2001. https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/10819/1/274013.pdf.

- Garde, Ruth. "Charged Bodies: Experiments with Electricity and the Human Body in the 18th Century." Brewminate, 2017. https://brewminate.com/charged-bodies-experiments-with-electricity-and-the-human-body-in-the-18th-century/.

- MacDonald, Helen. "Galvanising George Foster, 1803 [Edited Excerpt]." In Human Remains. Yale University Press: London, 2006.

- Montandon, Denys. "Frankenstein, the Aesthetic Failure." [In eng]. J Craniofac Surg 31, no. 7 (Oct 2020): 1857-60. https://doi.org/10.1097/scs.0000000000006687.

- "The Italian ‘Mad Scientist’ Whose Experiments Inspired Frankenstein." Italian Sons and Daughters of America (ISDA), October 31, 2019, https://orderisda.org/culture/literature/the-italian-mad-scientist-whose-experiments-inspired-frankenstein/.

- Naser, Nabil. "On Occasion of Seventy-Five Years of Cardiac Defibrillation in Humans." [In eng]. Acta Inform Med 31, no. 1 (Mar 2023): 68-72. https://doi.org/10.5455/aim.2023.31.68-72.

- Parent, André. "Giovanni Aldini: From Animal Electricity to Human Brain Stimulation." [In eng]. Can J Neurol Sci 31, no. 4 (Nov 2004): 576-84. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0317167100003851.

- "The Real Electric Frankenstein Experiments of the 1800s." Atlas Obscura, October 31, 2016, accessed August, 2024, https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/the-real-electric-frankenstein-experiments-of-the-1800s.

- Rogers, Kara. "Defibrillation." In Encyclopedia Britannica, 2009; last updated July 18, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/science/defibrillation.

- Ruston, Sharon. Shelley and Vitality. Houndmills [England]: Palgrave Macmillan in association with Arts and Humanities Research Board, 2005.

- ———. "The Science of Life and Death in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein." Public Domain Review, November 25, 2015. https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/the-science-of-life-and-death-in-mary-shelleys-frankenstein/.

Exhibit Details

Discover the scientific theories that inspired the animation of Frankenstein’s monster in Mary Shelley’s classic gothic horror novel, Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus. Researchers argued that galvanism, a sort of electricity they believed was the life force in all animals, could be used to resuscitate people, or possibly even reanimate a corpse. “How dangerous is the acquirement of knowledge (Ch. 4),” especially when a spark can generate life?

-

- Location

- Eckenhoff Reading Room

- Date

- Oct 7, 2024 - Apr 29, 2025

- Contact

- ghsl-specialcollections@northwestern.edu

- Subjects

- science

- 19th century

- 18th century

- literature