Introduction

Western thought during the time of George Washington was enamored with the philosophy of the Enlightenment. Based on rationalism, this movement produced theories and innovations across disciplines such as politics, science, medicine, and more. Intellectuals believed that humankind could solve all of its problems through the discovery of knowledge by reason and observation.

With this commitment to knowledge came new ways of disseminating information—such as newspapers and journals—that reached the educated class as well as those who had little formal education. Knowledge could be shared quickly and broadly, often provoking a shift in cultural norms faster than previously possible. At the same time, established theories and practices did not immediately disappear but continued in opposition to new findings or even hand-in-hand with them.

This exhibit accompanied the National Library of Medicine's traveling exhibition Every Necessary Care and Attention: George Washington & Medicine, which was on display at Galter Library November 21 - December 22, 2016.

Events

Lecture by Kelly Wisecup, Assistant Professor of English and American Studies and Science and Human Culture - “Medicine at Home: Early American Botanical Colonization and Native American Herbal Resistance”

Credits

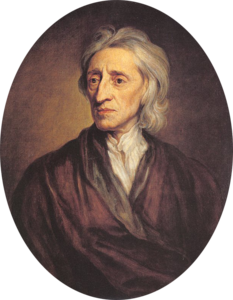

John Locke (1632-1704) championed the theory of empiricism, a new and influential doctrine arguing that knowledge is gained by sense observation and experience rather than deductive reasoning and intuition. Locke is most well-known for his treatises on politics and government in which he contends that people are by nature free and equal. Locke’s philosophy, especially his idea that government has limited power over people, and can be overthrown if it impinges on its citizens’ rights, impacted many American colonists who were arguing for equal representation in the British government or creation of their own state.

Item displayed: Locke, J. The Works of John Locke, Esq. 3rd ed. Vol. 2. London: printed for Edmund Parker, 1727.

Enlightenment Science

.jpg)

Isaac Newton (1642-1727) is well-known for his work in physics and calculus. Like Locke, he was an empiricist and applied this doctrine to his scientific work. Newton’s Opticks is an example of his dedication to empirically driven science. He presents the meticulously devised experiments and observed results that informed his conclusions with detailed illustrations. Newton’s works were immensely popular with academics and amateurs alike and influenced work in philosophy, theology, physics, mathematics, chemistry, and medicine.

Nature and Nature’s laws lay hid in night:

God said, ‘Let Newton be!’ and all was light.

Alexander Pope, eulogy couplet for Newton

Item displayed: Newton, I. Opticks: or, A treatise of the reflections, refractions, inflections, and colours of light. 3rd ed. London: printed for William and John Innys, 1721.

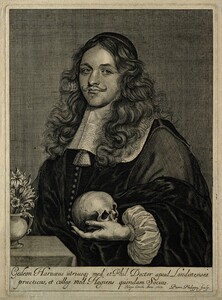

Newtonian medicine

Nicholas Robinson (c. 1697-1775) was a London physician originally from Wales. In the book displayed here, Robinson applies Newtonian principles of natural law and experimentation to medicine. He argues that free and open sharing of experiment results is in the best interest of the public and that advances in the treatment of disease should be available to the entire medical community. Robinson believed that practitioners who shroud their ‘miraculous’ cures in secrecy only intensify the public’s suspicion that physicians are solely interested in their own wealth and wellbeing.

Item displayed: Robinson, N. A new theory of physick and diseases, founded on the principles of the Newtonian philosophy. London: printed for C. Rivington, J. Lacy, and J. Clarke, 1725.

Preventive medicine for soldiers

Benjamin Rush’s (1746-1813) pamphlet discusses physical issues, such as personal hygiene and the proper diet, as well as mental health issues like keeping soldiers consistently engaged and active. It was reissued for distribution to officers in the Continental Army by order of the Board of War.

Fatal experience has taught the people of America that a greater proportion of men have perished with sickness in our armies than have fallen by the sword.

Item displayed: Rush, B. Directions for preserving the health of soldiers: recommended to the consideration of the officers of the Army of the United States. Lancaster, PA: John Dunlap, 1778.

Casualty Care

John Jones (1729-1791) was born in New York and from a young age studied medicine with his father and a cousin, both doctors. Jones published the first book on surgery in the American colonies, displayed here. He presents new surgical concepts and practices accompanied by personal experience as a

surgeon in the French and Indian Wars. This book shows an evolving view of combat medicine that includes humoral elements and observation-based care. For instance, he advocates treating major burns with bloodletting and enemas, but also favors quick removal of bullets, a novel idea in 1776.

Item displayed: Jones, J. Plain concise practical remarks, on the treatment of wounds and fractures: to which is added, an appendix, on camp and military hospitals; principally designed, for the use of young military and naval surgeons, in North America. Philadelphia: Robert Bell, 1776.

Concurrent with advances in science and philosophy were novel methods for disseminating information. Libraries, universities, clubs, and salons were founded. Journals, encyclopedias, and newspapers were established. New approaches to sharing knowledge allowed more people than ever before to access information.

Concurrent with advances in science and philosophy were novel methods for disseminating information. Libraries, universities, clubs, and salons were founded. Journals, encyclopedias, and newspapers were established. New approaches to sharing knowledge allowed more people than ever before to access information.

Thomas Paine’s (1737-1809) Common Sense, displayed here, went through 25 editions in 1776. It is estimated that every person in the American colonies had either read it or heard it read aloud.

Item displayed: Paine, T. Common sense; addressed to the inhabitants of America, on the following subjects. London: reprinted for J. Almon, 1776.

The first American medical journal

Journals, newspapers, and almanacs were important in the American colonies because they were often the only accessible sources of information. The Medical Repository was the first journal in the United States dedicated to the theory and practice of medicine, focusing especially on epidemics and contagious disease. It helped American physicians to establish and impact the profession independent of British influence.

Item displayed: Mitchell, SL. The Medical Repository. Vol. 1, no. 4, 1798.

Books for everyone

Books for everyone

Advances in printing press technology allowed printers to streamline production, making cheaper books, more quickly. More people could afford to buy books, and so more texts were written with the general reader in mind. Displayed here is Gideon Harvey’s popular guide for household medical care. George Washington had a copy of this book in his library at Mount Vernon.

Item displayed: Harvey, G. The family-physician, and the house apothecary. 2nd ed. rev. London: M.R., 1678.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Europe and its colonies wrestled with the progression from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance to the Enlightenment. While it is easy to think of these eras as distinct periods, the transition was complex and chaotic, marked by competing theories, ideas, and practices. This permeated all professions, including medicine. While some physicians clung to the methods and practices by which they had learned and experienced success, others took an experimental approach and disavowed old practices.

Humoral medicine

Re-balancing the body’s humors was a widespread practice systematized by ancient Greek doctors. Displayed here are instruments used to purge the body of the excess humor.

Spring lancet and scarificator. These instruments were developed for bleeding small veins. While bloodletting was an effective treatment for hypertension and a few other conditions, it was widely overused. Most 18th century advances in medical knowledge were in pathology, not treatment.

Trephine. Trephination is the process of drilling a hole in the skull to relieve pressure on the brain, and is one of the oldest known medical practices. Trephination was believed to heal those who suffered from epilepsy, mental disorders, and other ailments when the unhealthy humor escaped the hole.

Patent Medicine

Quacks, druggists, entrepreneurs, and anyone looking to make money sold enriching tonics, miraculous panaceas, and curative pills. Some patent medicines did have medicinal properties—e.g. ginger ale for indigestion—and others were harmless concoctions that might offer a placebo effect. But many contained opium, heroin, arsenic, or highproof alcohol. Patent medicine manufacturers were not required to disclose ingredients or substantiate efficacy. The pamphlet displayed here contains testimonials about a cure for scurvy, leprosy, ulcers, and other conditions. George Washington had a copy in his library at Mount Vernon.

Item displayed: Norton, J. An account of remarkable cures, performed by the use of Maredant’s antiscorbutic drops. London: 1772.

- "Books Owned by Washington." https://www.mountvernon.org/library/special-collections-archives/books-owned-by-washington/.

- Browne, Peadar. "Making Sense of Thomas Paine (1737-1809)." History Ireland 17, no. 5 (2009): 20-21. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40588415.

- Carr, E. F. "Early Medical Books in the Archibald Church Library Vii. Military and Naval Medicine and Surgery." Q Bull Northwest Univ Med Sch 22, no. 2 (Summer 1948): 164-8.

- Cassedy, James H. Medicine in America : A Short History. The American Moment. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991.

- Cox, Jim. "That Quacking Sound in Colonial America." Colonial Williamsburg Journal Spring (2004). https://research.colonialwilliamsburg.org/Foundation/journal/Spring04/quackery.cfm.

- Hagley Museum and Library. "The History of Patent Medicine [Online Exhibit]." 2016 Aug 1. http://www.hagley.org/online_exhibits/patentmed/history/history.html.

- Kahn, Richard J., and Patricia G. Kahn. "The Medical Repository--the First U.S. Medical Journal (1797-1824)." N Engl J Med 337, no. 26 (Dec 25 1997): 1926-30. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199712253372617.

- Kennedy, Michael. A Brief History of Disease, Science, and Medicine: From the Ice Age to the Genome Project. Mission Viejo, Calif: Asklepiad Press, 2004.

- King, Lester S. "A Glimpse into Eighteenth Century Medicine." Q Bull Northwest Univ Med Sch 36 (1962): 160.

- ———. Medical Thinking : A Historical Preface. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1982.

- Moore, Norman, and Claire L. Nutt. "Robinson, Nicholas (C. 1697–1775), Physician." Oxford University Press, 2004-09-23. https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-23861.

- Orr, H. Winnett. "Biographical Notes Regarding Some American Military Surgeons." Q Bull Northwest Univ Med Sch 20 (1946): 111.

- Pruitt, Basil A., Jr. "Combat Casualty Care and Surgical Progress." Ann Surg 243, no. 6 (Jun 2006): 715-29. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000220038.66466.b5.

- Rogers, Blair O. "Surgery in the Revolutionary War. Contributions of John Jones, M.D. (1729-1791)." Plastic and reconstructive surgery (1963) 49, no. 1 (1972): 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-197201000-00001.

- Rohrich, Rod J., and Daniel Sullivan. "The Revolution Begins: Reflections on Dr. Benjamin Rush." Plast Reconstr Surg 114, no. 3 (Sep 1 2004): 753-5. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.0000133458.10337.de.

- Shryock, Richard Harrison. "The Medical Reputation of Benjamin Rush: Contrasts over Two Centuries." Bulletin of the history of medicine 45, no. 6 (1971): 507-52.

- Sigelman, Lee, Colin Martindale, and Dean McKenzie. "The Common Style of 'Common Sense.'" Computers and the Humanities 30, no. 5 (1996): 373-79. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30204657.

- Smith, George. "Isaac Newton." In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta. Fall 2008, 2016 Jul 27 2008. http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2008/entries/newton.

- Uzgalis, William. "John Locke." In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta. Spring 2016, 2016 Jul 27 2016. http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2016/entries/locke/.

Exhibit Details

This exhibit presents a selection of the library's holdings to contextualize the western world at the time of George Washington, with an emphasis on medicine’s contemporary practices and developments.

-

- Location

- Library Atrium

- Date

- Nov 21, 2016 - Dec 22, 2016

- Contact

- ghsl-specialcollections@northwestern.edu

- Links

- Visit the NLM exhibit website

- Subjects

- surgery

- military medicine

- political history

- family medicine

.jpg)