Introduction

In the late 19th century, American medicine was focused on training physicians to treat the burgeoning population, especially in Chicago and the Midwest, which was still a developing, frontier area. Despite this need for doctors, many medical schools were reluctant to or fully prohibited the enrollment of non-white, non-male students.

Before the Civil War, only a dozen or so American medical schools had admitted students who identified as women, African American, Black, Indigenous, or other identities that have been historically marginalized in the US. In the post-war period, students from underrepresented minorities remained a tiny fraction of the total enrollment numbers. Progress was too slow, and so these communities, especially white women and African Americans, began to establish medical schools catering to their needs. Howard University opened its medical school in 1868; it was the first school founded especially for the education African American doctors, though it was open to people of any race or gender. By 1870, five women’s medical schools had been founded, the westernmost being the Woman’s Hospital Medical College of Chicago. Many more medical schools for Black and women students opened in the subsequent decades to accommodate the growing numbers of students.¹

This exhibit was put together to celebrate four physicians who charted their own paths in the pursuit of an MD. It showcases Mary Harris Thompson (MD 1870), Yasu Hishikawa (MD 1889), Carlos Montezuma (MD 1889), and Austin Curtis (MD 1891), who all received medical degrees from a Northwestern University affiliated medical school. In addition to their unique pathways in medicine, these graduates were chosen because of their impactful careers, their work attending to communities underserved by the medical establishment, and, in the case of Hishikawa and Curtis, because they are not featured elsewhere on campus.

This digital version of the exhibit adds staff-written biographical articles about each person, in addition to the poster, to offer more information and context about their lives. We hope to add to this series in the future.

Footnote

1. Nearly all women’s medical schools and black medical school in the United States closed in the early 20th century because of inadequate financial support, a condemnatory/condemning review in the Flexner Report, or because more mainstream medical schools began to accept non-traditional students. While enrollment numbers of underrepresented minorities/students remained low at most mainstream schools, the collective effect proved damaging for nearly all of the medical schools for African Americans and women.

Credits

Curated and designed by Katie Lattal, MA, Special Collections Librarian.

Wassaja, also known as Carlos Montezuma, MD (1869-1923)

MD Class of 1889, Chicago Medical College*

- Native American civil rights leader

- First Native American graduate of Chicago Medical College

- First Native American man to earn MD in the United States

*Predecessor of Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine

The biography below first appeared as a News Item on the Galter Library website on November 22, 2021 in celebration of Native American Heritage Month. We have added it here to expand on the exhibit poster content. You can read more about his medical practice on our main website.

Carlos Montezuma was the first Native American student to earn a degree from Northwestern University when he graduated in 1889 with an MD from Chicago Medical College, the medical department of Northwestern (now known as Feinberg School of Medicine). Montezuma lived a truly remarkable life, though he suffered immeasurable childhood trauma. He was originally named Wassaja (Was-SAH-jah), meaning signaling or beckoning, and his family were part of the Yavapai people who lived near Fort McDowell, in what the United States government then called the Arizona Territory. The Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation now occupies a small part of this ancestral territory in the mountainous area northeast of Phoenix.

In 1871, when he was five or six years old, Wassaja was captured by Tohono O'odham (Pima) raiders, separated from his family, and sold to Carlo Gentile. It was Gentile who renamed Wassaja "Carlos Montezuma," after himself. Early accounts of Montezuma's life depict the relationship between him and Gentile as paternal and warm—and it may have become like that over time—but Montezuma later recounted: "[I] had no idea what would become of me. I was sure of a cruel death or be made to work as a slave forever and ever."¹

Gentile—an Italian immigrant of some means who dabbled in mining gold and other pursuits in the American West before concentrating on photography—now brought Montezuma on his nonstop travels. In 1872 they stopped in Chicago, where Gentile worked in a gallery. Montezuma attended school, but also performed in one of Buffalo Bill Cody's first stage shows as "Azteka," a stereotypical Indian character (Gentile capitalized on the show; he was the ticket-taker, advertising agent, and sold souvenir photographs to show-goers). They toured with the show until March 1873, and returned to Chicago (and school) for a time. Then after several more years of travel, Gentile sent Montezuma to live with Rev. William H. Stedman in Urbana, IL, where he could have a more stable life.

Montezuma was just 14 years old when he matriculated at the University of Illinois in 1880. He wrote articles for the student newspaper and was the president of his class, as well as the president of the Adelphic Debate Society. In 1884 he graduated with a BS in Chemistry, the first Native American student to earn a degree from the University of Illinois. Immediately, Montezuma moved back to Chicago to pursue medicine. He was introduced to John H. Hollister, MD, a founder of Chicago Medical College and the professor of clinical medicine at that time, who promised to remit his tuition. In order to support himself through school, Montezuma worked at a pharmacy and received some financial help from friends. He was originally part of the Class of 1888, but it took him 5 years to finish school because he had to work so much. He officially graduated in 1889, though he built lifelong friendships with those in his original class, such as Charles Mayo. Montezuma became the second American Indian to earn an MD in the United States, the first being Susan La Flesche Picotte, MD (Omaha).

Montezuma first worked as a physician for the Indian Bureau. Within four years he had served at three different Indian Schools and reservations; he decried the squalid conditions of the schools and lack of medical supplies, and experienced a bit of culture shock since he had spent the last 20 years brought up by white people mostly in white urban settings. He finally ended up as the physician at the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania where he stayed for several years. Working at Carlisle brought him closer to Richard Pratt (who had founded the institution in 1879), with whom he had been corresponding since medical school. Montezuma already believed that Indian assimilation into white American culture was the best path to progress for American Indians, and closer proximity to Pratt further fed this belief. Montezuma stayed at Carlisle for three years, and he even served as physician to the famous Carlisle football team.²

Montezuma returned to Chicago late in 1895, where he reconnected with a medical school classmate, Fenton Turck. Turck brought Montezuma in to his private practice and he became a specialist in gastrointestinal disease. Montezuma made Chicago his home for the rest of his life, and more and more he began to reconnect with his Yavapai roots and his identity as Wassaja. This set in motion a major shift in his beliefs, namely, that the Indian Bureau and reservation system needed to be abolished due to the paternalism of the former and the segregation enacted by the latter.

Instead of total assimilation, Montezuma turned his activism toward Native American civil rights. He had years of experience writing and speaking about his life and beliefs—lectures on American Indian life was one of his paid gigs in medical school, and remember that he was the president of a debate club in college—and he now employed these skills to advocate for the land and water rights of the Yavapais and other Arizona tribes. Montezuma was a founding member of the Society of American Indians (SAI), a diverse group of leading Native progressives and non-native allies who formed the coalition to fight for American Indian interests. The society often clashed on policy and methodology since their specific goals so often differed, but as scholar Tsianina Lomawaima wrote, they firmly supported an "individual Indian’s right to full, valued contribution to the nation's social, economic, and political life."³ From 1915 to 1922, Montezuma published his own newsletter called, Wassaja: Freedom's Signal for the Indians, which served as his mouthpiece for his views on social justice for Native Americans and his criticism of the Indian Bureau and the SAI.

Montezuma married Marie Keller in 1913, and continued practicing medicine and advocacy work throughout the rest of his life. He opposed the government sending Native soldiers to fight in World War I when they were denied US citizenship, and continued to fight the Indian Bureau over Yavapai land and water rights. He was ultimately successful in ensuring the Yavapai had their own reservation on a portion of their ancestral lands and were not forced onto the nearby Salt River Pima-Maricopa Reservation. In late 1922, Montezuma contracted tuberculosis and realized he was dying. He decided to spend his remaining months in Fort McDowell with his extended family. He died on January 31, 1923.

By: Katie Lattal, Special Collections Librarian

Endnotes

- Montezuma and Larner, The Papers of Carlos Montezuma, Reel 2, October 7, 1905.

- Carlisle famously beat an undefeated Northwestern in 1903 and their quarterback, Jimmy Johnson, was named to the All-American team that year. Following graduation from Carlisle, Johnson enrolled at Northwestern University Dental School and also played for the Northwestern squad. He earned his DDS in 1907 and returned to Carlisle as assistant coach, where he helped train Jim Thorpe, one of the greatest athletes of the 20th century. He practiced dentistry thereafter.

- Lomawaima, “The Mutuality of Citizenship and Sovereignty,” 335.

Yasu Hishikawa, MD (circa 1860 - circa 1900-02)

MD Class of 1889, Woman's Medical College of Chicago*

- First Asian graduate of the Woman's Medical College of Chicago

- First Japanese woman to receive a medical license in Illinois

- One of the first woman physicians in Japan

- Specialized in women's and children's health

*This college affiliated with Northwestern University in 1892 to become Northwestern University Woman's Medical School.

The biography below first appeared as a News Item on the Galter Library website on March 25, 2022 in celebration of Women's History Month. We have added it here to expand on the exhibit poster content.

Yasu Hishikawa was born in Nagoya, Japan, around the year 1861, a time of great change for the country. In 1854, Japan had been forced to sign the Convention of Kanagawa, which opened it to the Western world, ending 220 years of isolationism. Fourteen years later, the Meiji Restoration of 1868 restored power to the emperor after nearly 700 years of de facto military rule by shoguns. Under Emperor Meiji, who ruled until 1912, Japan became an industrialized world power that, no longer isolated from the Western world, incorporated many Western ideas into its reshaped government and society.

Seeing this new openness to the West, Christian missionaries began to travel to Japan in the 1860s and '70s to establish missions and schools. The Japanese government encouraged foreign education of Japanese children as part of the country's efforts to modernize and to gain acceptance from Western countries. Although emphasis was placed on the education of boys, female missionaries opened schools expressly for girls across the country. Yasu Hishikawa attended one such school, the Kyōritsu jogakkō (Kyōritsu Girls' School) in Yokohama, which was founded by the Woman's Union Missionary Society in 1871.

Hishikawa wanted to study medicine but women in Japan were not permitted to attend medical school or take exams to be doctors; they had to attend foreign medical schools and return to their country, where they could then be exempted from taking the exams. In 1883, Sarah K. Cummings, MD, a graduate of the Woman's Medical College of Chicago (which became Northwestern University Woman's Medical School in 1892), was sent to Japan by the Woman's Presbyterian Board of Missions as its first female medical missionary. Because of Hishikawa's interest in medicine, another missionary introduced her to Cummings, and they started work together at a mission in Kanazawa. Hishikawa helped Cummings teach at schools for boys and girls and she learned about medicine by working in the mission's dispensary.

In 1884, Cummings established a scholarship at the Woman's Medical College in Chicago and helped Hishikawa secure a spot at the school, where she enrolled in 1886. While studying in Chicago, Hishikawa received the support of George E. Shipman, a prominent medical practitioner and lecturer as well as a philanthropist. When she graduated from WMC in 1889, Hishikawa was described as "one of its best students, having passed the highest examination in Medical Jurisprudence."¹ Although she officially attended the Woman's Medical College, she is generally considered the first Asian student to earn an MD from Northwestern University because, when the college was absorbed by Northwestern in 1892–three years after Hishikawa's graduation–all graduates of WMC retroactively became alumnae of Northwestern.

After receiving her degree, Hishikawa became the first Japanese woman to earn a medical license in the state of Illinois and was one of just 300 women practicing medicine in the state in the 1890s. Specializing in gynecology and pediatrics, she was an assistant house physician at the Foundlings' Home in Chicago and pursued a partial course of study as an intern at the Woman's Hospital. In November of 1890 she returned to Japan as a medical missionary. Before her departure, WMC president Charles Warrington Earle, MD, threw her a going-away party at his home.

When Hishikawa registered as a medical doctor in Japan in 1891, she was one of only 13 female doctors in the country. She began work in the Nigeshi Hospital in Yokohama, which was managed by a Christian organization. Within a few years she had begun working in the Kyoto Mission with her mentor Sarah Cummings, now known by her married name, Sarah Porter. Hishikawa established and ran a dispensary at the Mission, where they treated 1500 patients in one year.

While Yasu Hishikawa's date of death is unknown, mentions of her being ill appear in reports for the Kyoto Mission. According to the reports, the dispensary had to be closed for periods of time between 1894 and 1896 due to her illness. She had died by June 1902, when the journal Woman's Missionary Friend reported that she had died since returning to Japan in 1890.²

Besides the details discussed here, little is known about the life of Yasu Hishikawa. Thank you to researcher Takako Day, who compiled much of what is known about Hishikawa in her two-part article "Atypical Japanese Women - The First Japanese Female Medical Doctor and Nurses in Chicago." Without her work and generosity in sharing it, we would know very little about Yasu Hishikawa.

By: Emma Florio, Archives & Research Specialist

Endnotes

- Smith, Woman's Medical School, 145.

- Barnes, "College Girls in Missions," 195.

Mary Harris Thompson, MD (1829-1895)

MD Class of 1863, New England Female Medical College, Boston

MD ad eundem Class of 1870, Chicago Medical College*

- Founder, Surgeon, and Head Physician, Chicago Hospital for Women and Children, 1865-1895

- The hospital did not integrate men into the staff until 1972; it closed in 1988 due to financial reasons

- First woman awarded a degree from Chicago Medical College

- Founder, Woman's Hospital Medical College of Chicago, 1870

*Predecessor of Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine

The biography below was prepared for the bulletin of the August 2017 investiture of the Mary Harris Thompson, MD, Professorship. We have added it here to expand on the exhibit poster content.

Mary Harris Thompson was born in rural New York state in 1829. To help put herself through secondary school, Thompson started teaching at 15 years old. She was particularly adept in instruction, both of herself and of others: she taught herself Latin and math at a young age, and later studied scientific subjects in her spare time to develop courses for her students. After becoming interested in physiology and anatomy through these studies, she decided to pursue a career in medicine. In 1863 she earned her MD from the New England Female Medical College in Boston and gained practical experience treating patients at the New York Infirmary for Women and Children under the guidance of Drs. Emily and Elizabeth Blackwell.

Thompson decided to start her practice in Chicago because she knew there were few female doctors there, and after her arrival in the city, she observed an acute need for a hospital dedicated to women’s and children’s health. In 1865 she founded the Chicago Hospital for Women and Children, the first hospital staffed by female physicians, and served as head surgeon and physician until her death in 1895.

In 1869 she and three other women attended courses at Chicago Medical College, the predecessor to Feinberg School of Medicine. The admittance of these women was viewed as an experiment in co-education, and soon many male students complained that their presence inhibited discussion of certain 'indecent' topics and thus impeded their own medical education. Thompson and the other women were not allowed to return to classes. Because Thompson had already earned her MD in Boston, at the end of the 1869-70 school year she was granted an ad eundem degree from Northwestern, a customary practice at the time. She was the first woman to earn a degree from the medical school, and remained so until it became fully co-ed in 1926.

Thompson was frustrated at the impediments to women's medical education and with the support of a former instructor, Dr. William Byford, established the Woman's Medical College, which was to be affiliated with Thompson's hospital.

In 1871 the hospital was destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire. Thompson and her staff were able to save all their patients: they sent home those who were able to walk, and they moved bedridden patients first to a home in Lincoln Park, which was subsequently consumed by the fire, and then out to the prairie. Because of the great need for medical facilities post-fire, the hospital promptly received relief funds to re-establish itself.

Two weeks after celebrating the 30th anniversary of the hospital she founded, Thompson suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and died at the age of 66. The hospital was renamed the Mary Thompson Hospital in her honor and it remained in operation on the west side of Chicago until 1988.

By: Katie Lattal, Special Collections Librarian

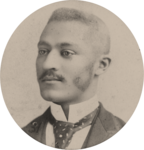

Austin M. Curtis, MD (1868-1939)

MD Class of 1891, Chicago Medical College*

- First intern, Provident Hospital, Chicago

- Surgeon-in-Chief, 1898-1902, Freedmen's Hospital, Washington, D.C.

- Chair of Surgery, 1928-1936, Howard University School of Medicine

*Predecessor of Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine

The biography below first appeared as a News Item on the Galter Library website on February 17, 2022 in celebration of Black History Month. We have added it here to expand on the exhibit poster content.

Austin Maurice Curtis was born in 1868 in Raleigh, NC, to Eleanora and Alexander Curtis. He attended college at Lincoln University, where he met his wife, Namahyoke "Namah" Sockum. They eloped in 1888, the year Curtis earned his B.A. Curtis moved to Chicago to attend Northwestern University Medical School, and Namah joined him after her family found out she had married.

In 1891 Curtis earned his MD from Northwestern and became the first intern to serve at the newly opened Provident Hospital. He became the first Black physician to receive a staff appointment at a de facto white hospital when he was brought on as an attending surgeon at Cook County Hospital in 1896. While on staff at Provident and Cook County, Curtis maintained a private surgical practice. He became a highly respected surgeon due to the abundant and varied training he received while working at the hospitals and his mentorship under Daniel Hale Williams, an accomplished and renowned Chicago surgeon. Curtis followed in Williams' footsteps when he succeeded Williams in the position of Surgeon-in-Chief at Freedmen's Hospital in Washington, DC.

Curtis led Freedmen's for four years, at which point he stepped down to focus on his private practice and his faculty position at Howard University Medical School (Freedmen's was the teaching hospital for Howard). He rose in the ranks at Howard becoming the first Black chair and fourth chair ever of the Department of Surgery in 1928. Curtis held this position for eight years, steering the department through the worst of the Great Depression. He served as a faculty member at Howard for 40 years.

In addition to his skill as a surgeon, Curtis left a legacy in his role as an educator. At Howard, he was highly regarded for his clinical instruction, particularly because he demonstrated to students how important attention to detail and keen observation were to surgical success. At a time when imaging was still in its infancy and hospital laboratories did not yet offer many diagnostic tests, observation and detailed medical history were paramount for accurate diagnoses, and thus successful operations. Curtis' educational reach extended beyond Howard when he became one of the earliest participants in the surgical clinics that took place during the annual meetings of the National Medical Association, the first professional organization to serve Black physicians in the US (the American Medical Association was racially segregated at the time). These clinics "offered Section members the opportunity to develop cognitive and motor skills in surgical diagnosis and operative techniques under the supervision of leading black surgeons."¹

Austin and Namah Curtis had three sons and a daughter who were prominent and active community members in both Chicago and Washington. Austin participated in a variety of civic clubs and leagues, and Namah—in addition to her roles as wife and mother—was involved in relief work, public service, activism, and politics. When the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898, yellow fever began to spread rampantly in the US encampments. Because of her organizing skills and political insight, Namah was tapped to recruit and lead Black women who, like her, had recovered from yellow fever and were considered fully immune, to serve as contract nurses in Cuba. Namah was recognized for her service with a high commendation, a lifelong government pension, and burial in Arlington National Cemetery.

These efforts contributed to the long process of acceptance of women nurses in the armed forces. The Curtises' sons followed in their father's stead by becoming physicians (all trained at Howard no less), and their mother's by serving as commissioned officers in World War I. Curtis opened a private surgical hospital and his oldest son, Arthur, to provide the Black community in Washington, DC, with a healthcare option other than home care or Freedmen's.

Austin Curtis passed away in 1939 in Washington, DC, leaving behind an indelible influence on American medicine. He impacted thousands of lives—from the patients he treated to the students he taught—and he played a crucial role in building healthcare infrastructure for communities deliberately left out by the medical establishment.

By: Katie Lattal, Special Collections Librarian

Endnotes

- William Matory in A Century of Black Surgeons, 460.

Archival Sources

- Carlos Montezuma papers 1888-1936 (bulk 1888-1922), Edward E. Ayer Manuscript Collection. Newberry Library, Chicago. https://collections.newberry.org/asset-management/2KXJ8ZPB3VPO

- Carlos Montezuma's Wassaja Newsletter, Carlos Montezuma collection, 1887-1980 (bulk 1887-1922). MS CM MSS 60, Arizona Collection. Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ. http://hdl.handle.net/2286/R.C.195

- Chicago Medical School Class of 1888. Class Composite Portrait Collection. Galter Health Sciences Library & Learning Center, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

- Chicago Medical School Class of 1891. Class Composite Portrait Collection. Galter Health Sciences Library & Learning Center, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

- Choate, John N. Carlos Montezuma seated on Carlisle school hospital steps with six women, possibly two nurses and four hospital aides SEP1893 [black and white gelatin glass negative]. National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Photo Lot 81-12 06912100. https://www.si.edu/object/carlos-montezuma-seated-carlisle-school-hospital-steps-six-women-possibly-two-nurses-and-four%3Asiris_arc_74350

- Montezuma, Carlos, and John W. Larner. The Papers of Carlos Montezuma, M.D.: Including the Papers of Maria Keller Montezuma Moore and the Papers of Joseph W. Latimer. Wilmington, Del: Scholarly Resources, 1983.

- Portrait (Front) of Wassaja (Beckoning) 1874 [hand-colored lantern slide]. National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Photo Lot 73 06702600. https://www.si.edu/object/portrait-front-wassaja-beckoning-1874%3Asiris_arc_73017

- The Woman's Union Missionary Society in Japan, Bible Training School [postcard]. N.d. "Glimpses of Japan," scrapbook 46-2. Woman's Union Missionary Society (Collection 379). Records, 1860-1983. The Billy Graham Center Archives, Wheaton College, Wheaton, IL.

- 'Yasso' for Miss Doremus [photograph]. N.d. Photo file. Woman's Union Missionary Society (Collection 379). Records, 1860-1983. The Billy Graham Center Archives, Wheaton College, Wheaton, IL.

Published Sources

- "A Hospital Staffed Only by Women for 100 Years." JAMA 193, no. 6 (1965): 30-31. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1965.03090060152041.

- "A Japanese Reception." The Daily Inter Ocean, November 22, 1890.

- "A Japanese Woman Doctor: Novel Reception at Dr. Charles W. Earle’s House." The Chicago Daily Tribune, November 22, 1890.

- Barnes, Io. "College Girls in Missions. VI. Northwestern University." Woman's missionary friend 34, no. 6 (1902): 192-95. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112109813177&view=1up&seq=207&skin=2021&q1=yasu.

- Beatty, William K. "Mary Harris Thompson—Pioneer Surgeon and Hospital Founder." The Proceedings of the Institute of Medicine of Chicago 34, no. 3 (1981): 83-86.

- Cobb, W. M. "Austin Maurice Curtis, 1868-1939." J Natl Med Assoc 46, no. 4 (Jul 1954): 294-8.

- Crandall, Maurice. "Carlos Montezuma and the Emergence of American Indian Activism." Oxford University Press, March 28, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.499.

- Cummings, Sarah K. "So Much to Be Done." Woman's Work for Woman 14, no. 3 (March 1884): 82-83.

- Cutler, H.G. Medical and Dental Colleges of the West: Historical and Biographical: Illustrated in Photogravure and Steel: Chicago. Chicago: The Oxford Publishing Company, 1896. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiuo.ark:/13960/t1xd26057.

- Day, Takako. "Atypical Japanese Women - the First Japanese Female Medical Doctor and Nurses in Chicago, Parts 1 and 2." Discover Nikkei. (December 6-7 2018). https://discovernikkei.org/ja/journal/2018/12/6/atypical-japanese-women-1/.

- "Dr. Curtis to Remain—Eminent Surgeon Locates in Washington." The Colored American (Washington, D.C.), February 15, 1902.

- Elmore, Joyce Ann. "Nurses in American History: Black Nurses: Their Service and Their Struggle." The American Journal of Nursing 76, no. 3 (1976): 435-37. https://doi.org/10.2307/3423888.

- French, Daniel Chester. "Bust of Mary Harris Thompson, M.D.", Art Institute of Chicago, 1902. Sculpture. https://www.artic.edu/artworks/118570/bust-of-mary-harris-thompson-m-d.

- Fujimoto, Hiro. "Women, Missionaries, and Medical Professions: The History of Overseas Female Students in Meiji Japan." Japan forum (Oxford, England) 32, no. 2 (2020): 185-208. https://doi.org/10.1080/09555803.2018.1516688.

- History of Medicine and Surgery and Physicians and Surgeons of Chicago. Chicago: The Biographical Publishing Corporation, 1922.

- In Memoriam, Mary Harris Thompson: Founder, Head Physician and Surgeon of the Mary Thompson Hospital of Chicago for Women and Children, May 1865-May 1895. Chicago: Board of Managers, 1896. https://archive.org/details/inmemoriammaryh00chic/mode/2up.

- Iverson, Peter. Carlos Montezuma and the Changing World of American Indians. 1st ed. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1982.

- Larner, John W., ed. The Papers of Carlos Montezuma, M.D.: Including the Papers of Maria Keller Montezuma Moore and the Papers of Joseph W. Latimer. Microfilm Edition ed. Wilmington, Del: Scholarly Resources, Inc., 1984.

- "Namahyoke Sockum Curtis in the Spanish-American War." WednesdaysWomen.com, Updated October 7, 2020. https://wednesdayswomen.com/namahyoke-sockum-curtis-in-the-spanish-american-war/.

- Lomawaima, K. Tsianina. "The Mutuality of Citizenship and Sovereignty: The Society of American Indians and the Battle to Inherit American." Studies in American Indian Literatures 25, no. 2 (Summer 2013): 331-51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5250/studamerindilite.25.2.0333.

- Morais, Herbert M. The History of the Negro in Medicine. International Library of Negro Life and History. 3rd ed. New York: Publishers Co., 1969.

- Murphy, Beverly. Black History Month: A Medical Perspective: Education [LibGuide]. Accessed May 17, 2024. https://guides.mclibrary.duke.edu/blackhistorymonth/education.

- Neumann, Caryn E. "Curtis, Namahyoke Sockum." Oxford University Press, May 31, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1093/acref/9780195301731.013.38346.

- Organ, Claude H., and Margaret M. Kosiba. A Century of Black Surgeons: The U.S.A. Experience. 1st ed. Norman, Okla: Transcript Press, 1987.

- Rothstein, William G. American Medical Schools and the Practice of Medicine: A History. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

- Rudavsky, Shari. "Curtis, Austin Maurice." Oxford University Press, May 31, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1093/acref/9780195301731.013.35238.

- Sammons, Vivian, ed. Blacks in Science and Medicine. New York: Hemisphere Pub. Corp., 1989.

- Schultz, Rima Lunin, and Adele Hast, eds. Women Building Chicago, 1790-1990: A Biographical Dictionary. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2001.

- Scott, Emmett J., and Newton Diehl Baker. Scott's Official History of the American Negro in the World War. Chicago: Homewood Press, 1919. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/007703000

- Smith, Avis E., Eliza H. Root, H. G. Cutler, and Marie J. Mergler. Woman's Medical School, Northwestern University: (Woman's Medical College of Chicago): The Institution and Its Founders: Class Histories, 1870-1896. Woman's Medical College of Chicago. Chicago: H. G. Cutler, 1896.

- Speroff, Leon. Carlos Montezuma, M.D.: A Yavapai American Hero: The Life and Times of an American Indian, 1866-1923. Portland, OR: Arnica Pub., 2003.

- Sperry, F. M. A Group of Distinguished Physicians and Surgeons of Chicago; a Collection of Biographical Sketches of Many of the Eminent Representatives, Past and Present, of the Medical Profession of Chicago. Chicago: J.H. Beers & Co., 1904.

- United States Congress House of Representatives. "Miscellaneous Reports. Part 1. Bureau Officers, Etc.," Annual reports of the Department of the Interior for the fiscal year ended June 30, 1900. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1900. https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/SERIALSET-04103_00_00-001-0005-0001/summary

- "Yasu Hishikawa." Medical Woman’s Journal 53 (August 1946): 54.

- "菱川やす4[Yasu Hishikawa 4]." 広瀬院長の弘前ブログ [Hirosaki’s Blog], hiroseorth.blogspot.com, March 2, 2019, https://hiroseorth.blogspot.com/2019/03/blog-post_2.html.

Exhibit Details

Features four early graduates of the medical school, highlighting their backgrounds and cultural identities, which were especially underrepresented in mid- to late 19th century American medicine, their accomplishments, and the different directions their medical careers took them.

-

- Location

- Second Floor Window Display

- Date

- Apr 1, 2021 - Present

- Contact

- ghsl-specialcollections@northwestern.edu

- Subjects

- northwestern

- biography

- 19th century